Why can't airlines survive without frequent flyer programs?

A loyalty program is a measure to provide benefits to good customers who purchase a lot of products or use a lot of services. A type of loyalty program is the 'mileage program' developed by airlines, where 'miles' are accumulated according to the flight distance and the class booked, and benefits are obtained according to the miles. The Wall Street Journal, an American economic newspaper, explains in a movie why airlines continue to adopt mileage programs.

Where air travel used to be a luxurious experience with complimentary cocktails and in-flight piano tunes, today it's the full complement of packed planes, limited luggage space and kicking children behind the seat you paid extra for.

To understand this shift, we need to go back to the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978, passed by the US Congress. This deregulation allowed airlines to set their own flights and routes, which created competition for profits and market share, leading to the first airline loyalty programs.

At the time of writing, American airlines were only making an average of $13 (about 2,000 yen) per passenger, but the situation in 2020 made it clear that loyalty programs were worth more than the airlines themselves.

In the late 1970s, American Airlines was losing its market clout.

Deregulation allowed new smaller airlines to gain market share with lower prices, forcing traditional airlines to find ways to maintain their prices and avoid losing customers while still serving the same routes.

After receiving the proposal from the advertising agency, American Airlines put together a small team, including then-CEO Bob Crandall and outside consultant Hal Brierley, to begin developing ideas.

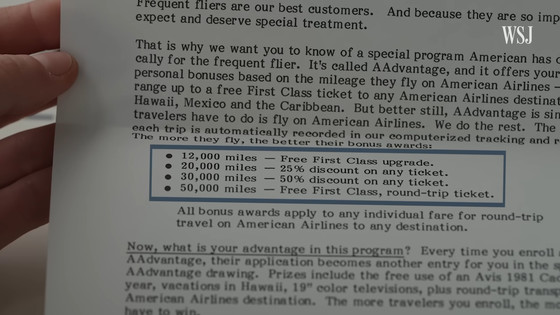

Inspired by retail rewards schemes, the team came up with an early version of Advantage, which rewarded customers with points called 'miles.' The first reward was simply a free flight.

American Airlines expected the business value the program would attract would exceed the cost of redeeming rewards.

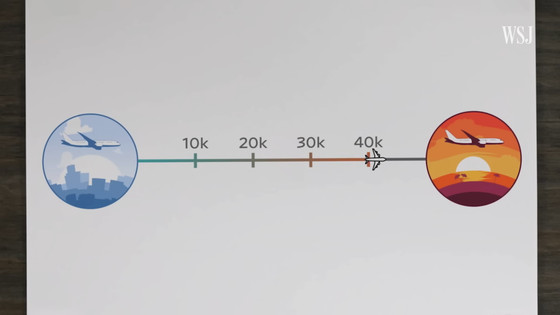

Knowing that the average consumer flies about 40,000 miles per year, the airline set the award threshold at 50,000 miles, imposed a one-year time limit on the program, and developed a way to track customers.

At the time, reservation systems were still new, and matching different flights for the same customer was a challenge. To solve this, American Airlines took a cue from car rental companies and used a system that assigned unique numbers to customers.

After more than a year of planning, American Airlines launched Advantage on May 1, 1981.

United Airlines followed American Airlines' lead a week later, and Trans World, Continental, Northwest Orient, Braniff and Texas International soon followed suit.

American Airlines was the first to offer a miles program, giving it a head start over other airlines: while other airlines were developing their mileage calculation systems, American Airlines had acquired 1 million customers, double its expectations.

But that changed when United Airlines launched its unlimited program, forcing American Airlines to also do away with its one-year limit, which led many heavy flyers to join multiple airline programs.

Airlines competed with each other to establish reward systems based on mileage, such as the Gold Program for the top 2% of customers, and perks like free upgrades to first class to get customers used to more expensive service.

Miles became a kind of currency and began to attract interest from outside the airline industry, particularly from banks: airlines sold miles to banks, who offered them as rewards to cardholders.

The pay-per-spend structure has made the program more like a bank, based not just on frequent flyers but also on spending.

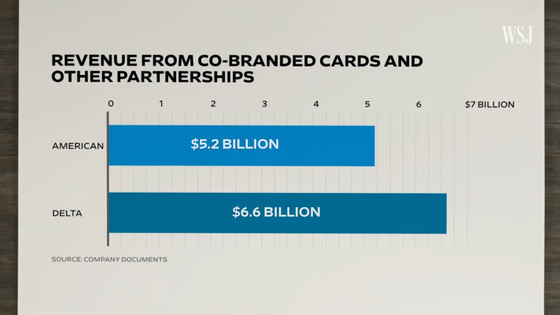

By 2023, American Airlines will earn $5.2 billion from affiliate cards and other sources, while Delta Airlines will earn $6.6 billion.

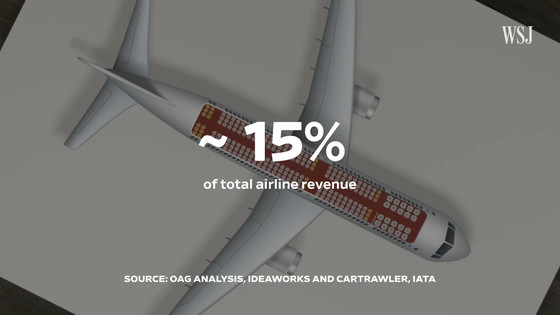

By 2022, ancillary revenue, such as seat upgrades and baggage fees, will account for roughly 15% of airlines' total revenue. To maintain their economic advantage, airlines are constantly adjusting their programs, making changes such as changing status criteria or increasing the number of miles required to fly.

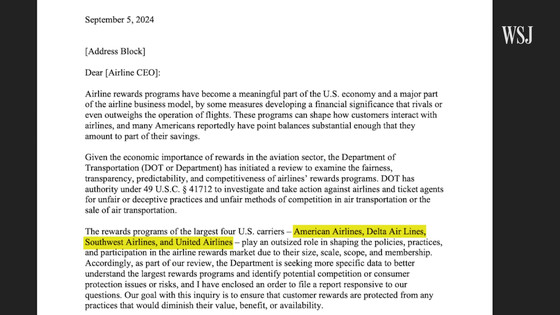

However, in 2024, the Department of Transportation launched an investigation into the four major airlines, American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Southwest Airlines, and United Airlines, alleging that their loyalty programs 'may be unfair, deceptive, or anticompetitive.'

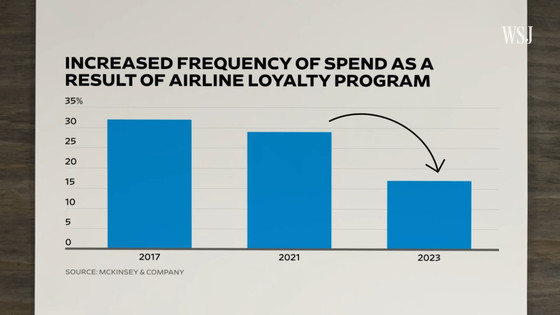

A study by the major consulting firm McKinsey found that the impact of these programs on changing passenger behavior declined from 2017 to 2021 and again from 2021 to 2023. This has led airlines like American Airlines to consider expanding where you can use your miles. Now you can earn them almost anywhere, but how much you can get for them remains a topic of debate.

Related Posts: