What is 'motor doping' in cycling that is a concern at the Olympics?

With the Paris Olympics coming up on July 26, 2024, officials and athletes are on edge about doping, but it's not just the use of drugs that is prohibited. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) has explained the reality of hidden electric motors, or 'motor doping,' which is a problem in cycling, and how to deal with it.

EV Motors Without Rare Earth Permanent Magnets - IEEE Spectrum

At the 'Routes de l'Oise' amateur bicycle race held in the suburbs of Paris in May 2024, a cyclist suspected of installing a motor on his bicycle fled in a van and fled about 100 meters with a race official who tried to stop him on the hood of the van , creating a scene straight out of a movie.

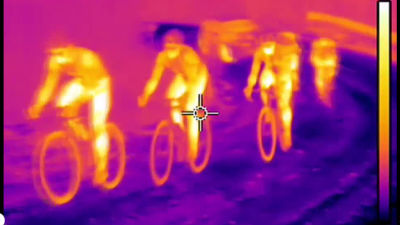

This type of cheating is known among cyclists as 'motor doping,' and electromagnetic scanners and X-ray machines are expected to be used to check for it during cycling events at the Paris Olympics.

In professional cycling, motor doping was confirmed once in 2016, and since then

Concerns about motor doping first surfaced in 2010, when Swiss cyclists used astonishing acceleration to win the European championships. At the time, the UCI didn't have the technology to detect hidden motors, and the infrared cameras hastily installed were not useful for pre- and post-race inspections, when the motors weren't generating heat.

Then, at the 2016 Cyclocross World Championships in Belgium, a trial iPad-based magnetic measurement tablet was used to identify a bike bearing the name of local racer Femke van den Driesch, which had a motor and battery built into the frame.

By Dimitri Maladry

Van den Driesch maintained his innocence but was banned for six years and retired from cycling, marking the first time a cyclist has been formally accused of mechanical doping.

However, magnetic tablets often gave false positives, and there have been cases where suspected bikes were found innocent after being dismantled, leading the UCI to

'The X-ray inspection equipment will eliminate any doubt regarding the race results,' the UCI said at a press conference at the time. It also revealed that the 2023 Tour de France will have nearly 1,000 motor doping tests, and that it will maintain a strict inspection system.

But X-ray machines aren't foolproof. According to Jean-Christophe Perrault, an Olympic silver medalist and former head of anti-cheating at the UCI, there are plenty of opportunities for riders to slip through the cracks at major races by bringing in a spare bike, so the only way to completely eliminate suspicion of cheating is to monitor the race in real time.

The UCI is already working with France's Atomic and Alternative Energies Commission (CEA) to introduce live monitoring technology that uses high-resolution magnetometers attached to bikes to detect hidden motor signals.

Fitting detectors to every racing bike won't be easy, but Perreault is convinced it's the only way. 'We've been talking about this for 10 years now,' he told IEEE. 'If we're going to solve this long-standing problem, we need to make an investment.'

Related Posts:

in Vehicle, Posted by log1l_ks