Whether you can master AI or not depends on your ability, and research shows that AI has increased the output of the top 10% of elite scientists by 81%

While the development of AI has raised concerns in the field of academic research about problems such as

Artificial Intelligence, Scientific Discovery, and Innovation

(PDF file) https://aidantr.github.io/files/AI_innovation.pdf

Recent AI paper cites evidence that AI positively impacts scientific R&D | Technology Law Dispatch

https://www.technologylawdispatch.com/2024/11/artificial-intelligence/recent-ai-paper-cites-evidence-that-ai-positively-impacts-scientific-rd/

The study participants were 1,018 research scientists working in materials science across a number of major US companies in fields such as medicine, engineering and manufacturing. They were given an AI tool that would generate recipes for new compounds that were predicted to have specific properties.

The tool was built from a graph neural network (GNN) trained on the structures and properties of existing materials, allowing the AI to represent materials as multidimensional graphs of atoms and bonds and learn the laws of physics to encode their properties at scale. Scientists could then evaluate the output of the AI tool to identify promising combinations and synthesize new materials.

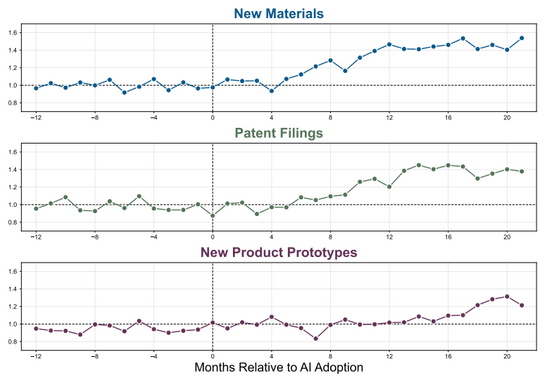

The study found that AI-assisted scientists discovered 44% more materials, which led to a 39% increase in patent applications. AI accelerated innovation, leading to a 17% increase in the development of product prototypes using new compounds.

The graph below illustrates this. The graph shows the trends in the number of new material discoveries (top), number of patent applications (middle), and number of product prototypes (bottom) after introducing AI (vertical line), with the average before AI set to 1. After introducing AI, the number of new material discoveries and patent applications increased within 5 to 6 months, and new products utilizing those discoveries were developed one to one and a half years later.

Taking into account the cost of implementing AI, this result translates into a 13-15% improvement in research and development efficiency.

'This result has two implications. First, it shows that there is potential for AI-driven research. Second, it confirms that these discoveries can lead to product innovation without becoming a complete bottleneck in late-stage R&D,' Tonner Rogers said.

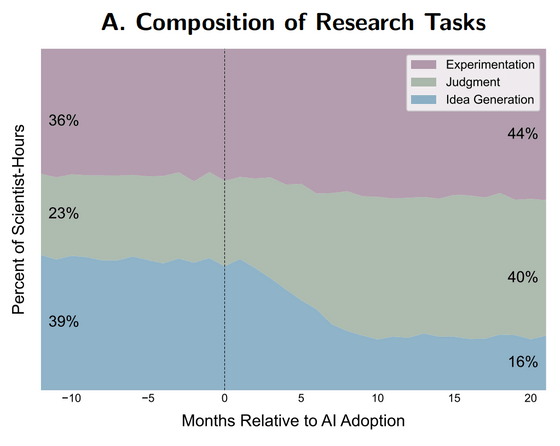

AI has dramatically changed the way scientists work, largely automating the process of generating ideas for new materials, but instead giving scientists a new task of evaluating candidates suggested by AI models.

Below is a diagram showing the time allocation of scientists' tasks on the vertical axis and the duration on the horizontal axis, with each task color-coded as idea generation (blue), evaluation (green), and experimentation (purple). Before AI was introduced, scientists spent about 40% of their time coming up with ideas for potential new materials, but with the introduction of AI, this fell to less than 16%. Meanwhile, the time spent examining candidates nearly doubled, and the time spent on experiments also increased.

The study also highlights that not all scientists have benefited equally from AI.

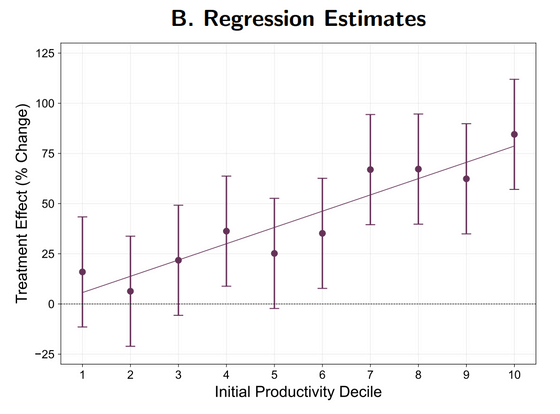

Below is a graph that plots the effect of AI on the vertical axis and the productivity of scientists on the horizontal axis. Scientists with lower productivity did not improve their performance much, but the top 10% of top scientists (far right) improved their performance by 81%.

While increasing productivity, AI has also made scientists' jobs more tedious.

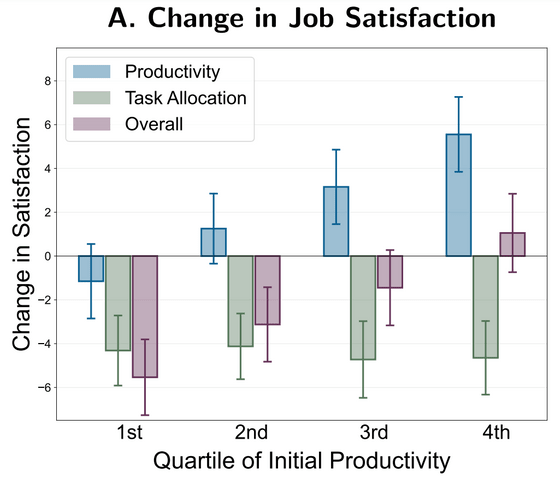

The figure below shows job satisfaction broken down by scientist productivity, color-coded according to 'changes in productivity (blue)', 'changes in task allocation (green)', and 'overall satisfaction (purple)'.

In the figure above, the least productive scientists (far left) experienced a decline in all satisfaction levels. Also, while the best scientists were satisfied with their increased productivity, their satisfaction was significantly hurt by the changes in task allocation, and overall satisfaction was either negative or only slightly increased even for the best scientists. Scientists may have found the process of coming up with ideas for potential new materials rewarding, and may have felt that this was being usurped by AI.

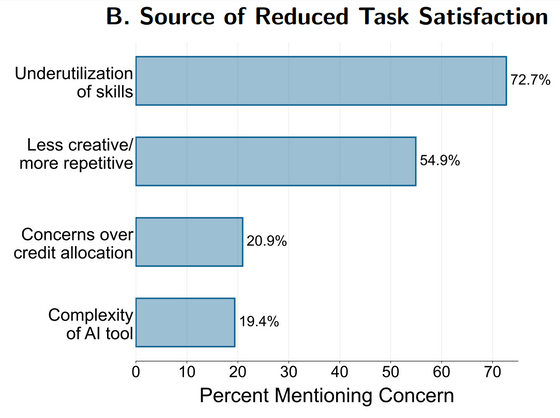

Supporting this, the scientists cited the following reasons for declining job satisfaction, in order: underutilization of skills (73%), reduced creativity and increased repetitive work (53%), problems attributing results (21%), and the complexity of AI tools (19%).

'I'm impressed with the capabilities of the AI tools, but I can't help but feel like a lot of the work I've done has been rendered worthless, because this is not how I'm experienced,' one scientist said of the AI tools.

'We find that AI can significantly accelerate the discovery of new materials, leading to more patent applications and improved product innovation. But this only works when combined with well-trained scientists, because top scientists can prioritize promising AI suggestions, while less knowledgeable scientists waste significant resources testing false positives,' Tonner Rogers wrote in their paper.

Related Posts: