An optical sensor will be developed that can capture high-definition images beyond physical limits without using any lenses

Imaging technology has supported breakthroughs ranging from mapping distant galaxies with radio telescope arrays to uncovering the fine structure inside cells. However, a fundamental barrier remains: the inability to capture high-resolution, wide-field images at visible wavelengths without cumbersome lenses or strict alignment constraints. A research team led by Guoan Zheng, director of the Center for Biomedical and Bioengineering Innovation (CBBI) at the University of Connecticut, has unveiled a groundbreaking solution that could redefine optical imaging across science, medicine, and industry.

Multiscale aperture synthesis imager | Nature Communications

New image sensor breaks optical limits

https://phys.org/news/2025-12-image-sensor-optical-limits.html

Synthetic aperture imaging, the technique that enabled the Event Horizon Telescope to image black holes, involves coherently combining measurements from multiple distant sensors to simulate a much larger imaging aperture.

In radio astronomy, this is possible because radio wavelengths are much longer, allowing precise synchronization between sensors. However, at visible light wavelengths, the scales involved are orders of magnitude smaller, making it physically impossible to meet the traditional synchronization requirements. This has been a 'long-standing technical challenge' for imaging technology, Zheng said.

The research team developed a method called the 'Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager' (MASI). Since perfectly synchronizing multiple optical sensors physically requires nanometer-level precision, MASI uses each sensor to measure light independently and synchronizes the data using a computational algorithm.

Below is an image of the surface of a bullet casing taken using MASI.

Jeng describes MASI as 'akin to multiple photographers taking pictures of the same scene, not as ordinary photographs but as raw measurements of light wave properties, and then using software to stitch these independent images together to create one super-high resolution image.'

The advent of MASI will eliminate the need for the 'rigorous interferometer setup' that has been an obstacle to the practical application of optical synthetic aperture systems.

MASI differs from conventional optical imaging in that, instead of using a lens to focus light onto a sensor, it deploys a coded sensor array positioned on different parts of a diffractive surface. The coded sensor array captures how light waves spread after interacting with an object, and then uses a computational algorithm to reconstruct how the light entered the object.

The pre- diffracted light waves are digitally padded to numerically propagate the wave field to the object plane, and then a computational phase synchronization technique is used to iteratively adjust the relative phase offset of each sensor data to maximize the overall coherence and energy of the joint reconstruction.

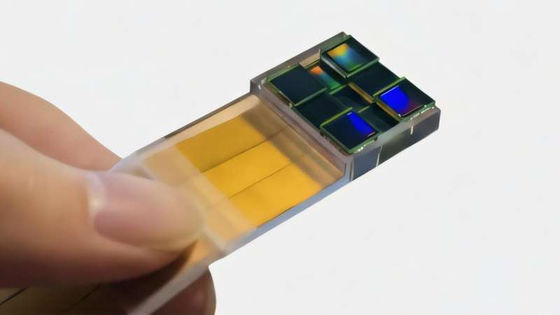

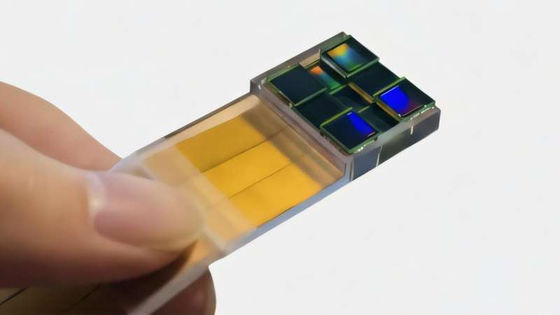

The appearance of MASI, a lensless image sensor, is as follows.

MASI overcomes the ' diffraction limit ' and other constraints that plague traditional optics by optimizing the combined wavefield in software rather than physically placing sensors. This allows for a virtual synthetic aperture that is larger than a single sensor, enabling high-definition image capture with sub-micron resolution without a lens.

MASI allows us to reconstruct images with submicron resolution by capturing diffraction patterns from a distance of just a few centimeters, without a lens—similar to being able to see the tiny ridges of a human hair from across a desk, rather than from a distance of just a few centimeters.

Regarding the applications and possibilities of MASI, Zheng said, 'The potential applications of MASI are diverse, ranging from forensics and medical diagnostics to industrial inspection and remote sensing.' 'But what's most exciting is its scalability. While traditional optical systems become exponentially more complex as they scale, our system scales linearly, potentially enabling large-scale arrays for previously unimaginable applications.'

Related Posts:

in Hardware, Posted by logu_ii