What are the 'paradoxes' of English education in Japan from the perspective of an American professor at the University of Tokyo who spent 40 years in Japan?

Professor

The English Paradox: Four Decades of Life and Language in Japan | TokyoDev

https://www.tokyodev.com/articles/the-english-paradox-four-decades-of-life-and-language-in-japan

·table of contents

◆1: English is not important in Japan

◆2: I'm surprisingly not interested in English

◆3: Fairness and uniformity

◆4: Changes facing foreign language education in Japan

◆5: Words that foreigners need to know when working in Japan

◆1: English is not important in Japan

When Gally moved to Tokyo in August 1983, he initially lived in an apartment complex for foreigners, surrounded by neighbors and friends who were fluent in English, and exposed to English newspapers, radio and films.

Although he saw Japanese on the streets and on trains, he mostly ignored it because he couldn't understand it. However, as he lived in Japan using only English, he naturally came to think that 'English is an important language that is essential to life in Japan.'

However, Gary's views gradually changed while living in Japan, and eventually he made a 180-degree turn.

Gary had an interest in foreign languages since his high school days, and majored in linguistics at university and graduate school. While working as an English teacher, he spent most of his time outside of work studying Japanese, and through intensive study he mastered the language in two years.

When Gary began his translation work, he strengthened his belief that English was important, because Japanese companies and government agencies flocked to him to translate and paid him generously, proving the economic value of English in Japan.

However, as he observed how his work was being treated by his Japanese clients, Gary gradually began to question his own thinking.

For example, one client asked Gulley to translate their company's brochure into English, but while thousands of copies of the Japanese brochure were printed, only 100 copies of the English version were printed. Also, a national theater asked Gulley to translate a play's program, but the finished booklet was 32 pages long, and Gulley's English translation took up only one page, and of course the play was in Japanese.

From these experiences, Gulley realized that while English does indeed have some economic value in Japan, its value is far less than the importance of the Japanese language.

'Becoming a translator and being able to read Japanese made me realize just how peripheral English is to life in Japan,' Gulley recalls.

Gary gradually began to use less English not only at work but also in his private life. Gary has two daughters, and when they were little, they only spoke English at home, but their mother tongue was Japanese. Therefore, when they started elementary school, they had to use Japanese to talk about school.

Eventually, Gary found himself rarely speaking English, except when speaking with his students in English conversation classes and when he visited his family in the U.S. once or twice a year.

◆2: I'm surprisingly not interested in English

After spending nearly 20 years in Japan as an English teacher and freelance translator, Gulley was hired by the University of Tokyo in 2005 to develop and run a course to help undergraduate students write scientific papers in English.

Having thus become fully involved in English education in Japan, Gulley noticed a stark difference in attitude between the government and universities, who wanted talented students to learn English as a global language, and the students themselves who were studying English.

Among the students under Gary's tutoring, there were a few who were enthusiastic about their writing classes, but most of them were not very interested in English and were more interested in getting credits than in acquiring English skills.

'Their cold attitude towards English stood in stark contrast to the enthusiasm of education leaders and authorities who preached about the importance of English proficiency in the 'age of globalisation,'' Gulley said.

by

Mr. Gulley also learned about the overall state of English education in Japan by visiting other universities and exchanging information with other educators. As a result, he found that the lack of interest in English was not unique to the University of Tokyo, but was a trend seen throughout Japanese universities.

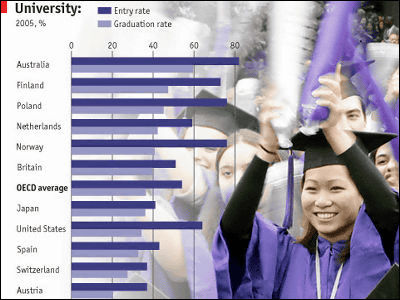

Moreover, not only were students at second- and third-tier universities less fluent than students at the University of Tokyo, but they also had far less interest in becoming fluent in English. With a handful of exceptions, students at Japan's top universities did not see English as useful for their futures, nor did they want to become fluent in it. As a result, their English skills remained at beginner level, and very few students graduated with a decent level of English.

What also surprised Gulley was the lack of interest young people in English-speaking culture.

Most of the older, fluent English speakers that Gally gets to know were people who had been engrossed in English-speaking media when they were younger, because American and British rock and pop music, Hollywood movies and TV shows were a major part of life in Japan in the 1950s and 1960s.

However, among the young people he meets, there are few students who are into American hip-hop or TV dramas, so he says many young people in Japan seem content with their own country's pop culture.

◆3: Fairness and uniformity

As time passed since he took up his post at the University of Tokyo and began teaching English to graduate students, Gallie's perspective on Japan's educational scene broadened even further, and he began to see a theme underlying the debate surrounding English education in Japan.

It is an unwritten rule that 'English education must be fair.'

Though it is rarely acknowledged, the recognition that all children should be able to learn English equally is an implicit understanding in discussions of English education in Japan, and is rarely questioned.

For example, while there has been debate about whether English classes should begin at age 10 or 12, the suggestion that the age at which English education should begin should be varied depending on the child's ability and wishes has not been considered.

Similarly, the introduction of

A uniform English education model is consistent not only at compulsory education level but also at many high school and university levels, and discussions of education assume that all children should follow the same curriculum and learning pace, regardless of students' learning methods or interests.

Regarding this, Gulley analyzes, 'Japan's English education policy is dominated by the concept of 'fairness.' Because academic background is important in Japanese society, policies that give preferential treatment to certain groups - such as the wealthy, those living in urban areas, children with highly educated parents, or children who happen to be fluent in English through self-study - will provoke a backlash from the public.'

◆4: Changes facing foreign language education in Japan

English alone is a challenge for Japan's education policy, but the number of non-English speakers in Japan is growing rapidly, creating a huge demand for people who can speak Chinese, Vietnamese and Nepalese, yet the Japanese education system devotes almost all of its resources to English alone, Gulley points out.

According to statistics from the Ministry of Justice, of the approximately 3 million foreigners living in Japan as of the end of 2023, the overwhelming majority are Chinese, at 820,000, growing by 8% per year. The second largest group is Vietnamese, at over 565,000, growing by 15.5%. In comparison, there are only 63,000 Americans living in Japan, growing by just 4.3%.

Another change facing Japan's education system is the development of technology, particularly AI. Machine translation has become more accurate, and large-scale language models can now translate texts naturally, but the Japanese government has had little discussion about the impact this technology will have on English education.

Gulley believes one attractive use of AI is that it could provide personalized, interactive learning experiences for each student, but he points out that implementing such technology in Japan, where fairness is paramount, would be extremely difficult.

◆5: Words that foreigners need to know when working in Japan

Gulley contributed this article to TokyoDev, a job site for international software developers looking to work in Japan.

Gally offered advice to those considering working in Japan, saying, 'Japanese people learn English mainly through studying textbooks and preparing for exams, and have had limited opportunities to use English as a natural communication tool. This is why some colleagues and clients may be hesitant to speak English in meetings or public, despite having studied English for years, while others have no qualms about writing documents or emails in English. Being aware of this will help you support your Japanese colleagues and build stronger working relationships.'

Related Posts:

in Note, Posted by log1l_ks