What are the harms and benefits of huge electronic waste processing plants that spew hazardous substances and pollute soil and rivers?

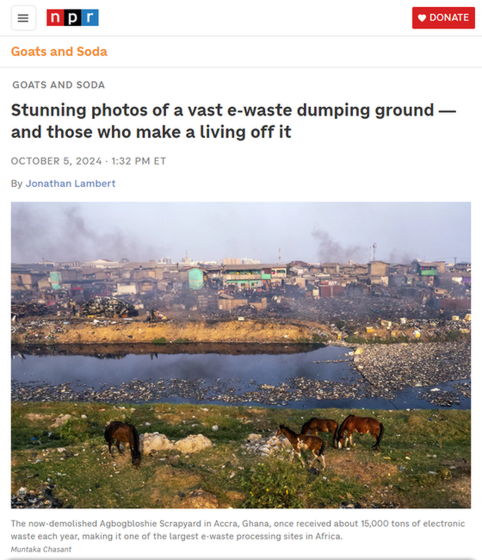

The Agbogbloshie scrapyard in Accra, the capital of Ghana, was one of the largest e-waste processing plants in Africa, receiving 15,000 tons of e-waste every year.

Here's photos of e-waste and discarded electronics in Ghana : Goats and Soda : NPR

https://www.npr.org/sections/goats-and-soda/2024/10/05/g-s1-6411/electronics-public-health-waste-ghana-phones-computers

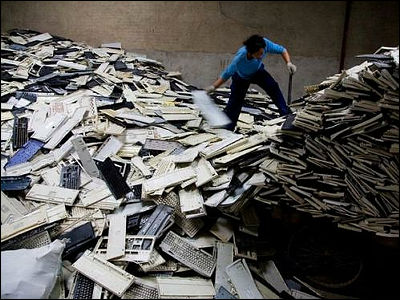

Emmanuel Akatile, a Ghanaian, was looking for work when he was 18 years old in the capital, Accra, about 500 miles (about 800 km) away from his hometown. The job he found at that time was 'searching for valuable scrap metal from piles of discarded electronic devices.' The monthly salary for searching for scrap metal at a waste disposal site was about $60 (about 8,900 yen). When asked why he took up the scrap collection job, Akatile said, 'After losing my parents, I started collecting scrap around 2021 to support my family,' and 'The area where I live has no electricity and is not well developed.'

Akatiele worked at the Agbogbloshie scrapyard, which was Africa's largest e-waste processing site for many years, processing 15,000 tonnes of used electronic devices such as mobile phones and computers annually. The site is rife with toxic chemicals that leach into the water and pollute the air, making scrap collection a very dangerous job.

The project, '

'Countries around the world can't just dump all their garbage at Agbogbloshie scrapyard because it has a really negative impact on people,' said Anas Aremeyaw Anas, a journalist and co-leader of the project. 'But there is a positive side to dumping e-waste at Agbogbloshie scrapyard.' The 'positive side' Anas is referring to is that it provides jobs to poor people like Akatile.

Electronic waste has become a global problem, and it is estimated that humanity will discard about 62 million tons of electronic devices in 2022. This is enough to fill the equator with trucks loaded with waste. According to UN estimates, this 62 million tons of electronic waste contains precious metals worth $91 billion (about 13.5 trillion yen), and scrap collectors like Akatile are working to recover this.

Electronic waste can be broadly divided into two categories: 'functional' and 'non-functional'. The boundary between the two is vague, and what is 'usable or repairable' for some may not be for others. International law prohibits the trade of 'non-functional electronic waste that contains toxic substances', but the United Nations considers the trade of 'functional electronic waste' to be 'beneficial because it can extend the life of products'.

The Ghana E-Waste project found that exporters working at the Agbogbloshie scrapyard were not separating functioning and non-functioning e-waste. 'If you have a container full of TV screens, how are you going to inspect each one and make sure they're working or not?' said journalist Benedict Kruzen, co-author of the project.

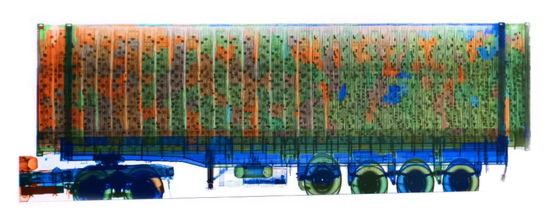

Below is an X-ray of a cargo truck loaded with e-waste passing through customs in Accra. According to the 'E-Waste in Ghana' project, they were able to detect illegal e-waste by scanning up to 120 cargo trucks per hour. Although the import of many types of hazardous e-waste is prohibited in Ghana, local customs officials are bribing people to allow the import of illegal e-waste.

As a result, Ghana's coastline is rife with unofficial e-waste dumps, where functioning and non-functioning e-waste are dumped in mountains without being separated. And at these sites, scrap collectors like Akatile are working to recover valuable precious metals from the waste.

Collecting electronic waste is dangerous work and can result in injuries such as cuts and burns. In addition, as mentioned above, electronic waste processing plants can emit toxic fumes.

According to Chasanto, co-author of the 'E-Waste in Ghana' project, most of the workers who collect scrap metal come from Ghana's Upper East region, where warming temperatures have upended traditional agricultural practices and 'youth unemployment is the highest in this region,' Chasanto said. He said young people from the Upper East region migrate to e-waste sites during the dry season to work.

Scrap collectors often incinerate waste to separate valuable minerals, such as copper wire and steel, from useless plastics. This process releases toxic fumes that can cause burns, cuts, and other injuries. Many e-waste workers are children, the project team noted.

According to Chasanto, many young people have died while collecting e-waste. 'Akanwee, who is a sickle cell carrier, never went near fires or collection work, but collecting e-waste was his only livelihood,' he said, revealing the current situation in which local residents have no choice but to work at the e-waste site every once in a while.

A scrap salvage worker burns electrical wire to salvage the copper.

In other cases, heavy metals contained in e-waste can seep into the soil and water, posing serious health risks to local communities. 'When people start burning their trash, toxic fumes can force them to relocate,' according to the project.

A worker collects recyclable plastic from discarded plastic. In some cases, toxic substances can leach into water, causing damage to local water supplies.

In parallel with these losses, a recycling and repair industry is booming in Ghana. There are also buyers looking to repair circuit boards or extract precious metals, and informal markets selling broken mobile phones, and the country's economy is thriving around this e-waste processing industry. According to the Ghana E-Waste project, Accra is home to hundreds of small, independent shops selling second-hand and refurbished equipment, from televisions to computers.

'In Africa, people still believe in repairing things - don't throw them away, you can still do something about them,' Kruzen said. 'In the West, we see these things as disposable, which is contributing to e-waste around the world.'

The most valuable precious metals extracted from e-waste rarely stay in Ghana, with most of it being exported to more advanced refineries in Europe and Asia.

Anas and the other project team members say they hope this project will encourage people to reconsider their relationship with the electronics in their lives. 'The materials that make your phone run only spend a moment in the processing plant. These materials travel all over the world. The electronics we have in our hands are the product of someone's sacrifice, somewhere in the world. They don't come for free,' Kruzen said.

Related Posts:

in Note, Posted by logu_ii