What was the mechanism behind sailing ships used in the 16th century, in the middle of the Age of Discovery?

During

How a 16th Century Explorer's Sailing Ship Works - YouTube

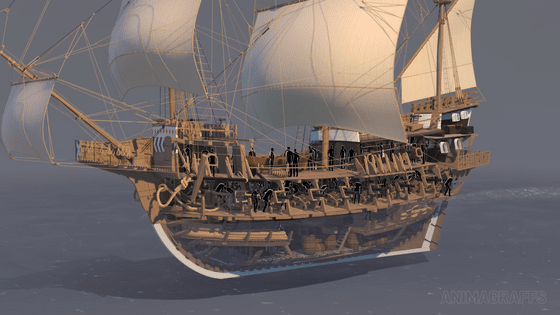

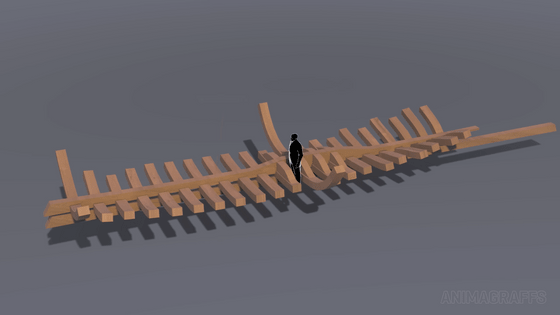

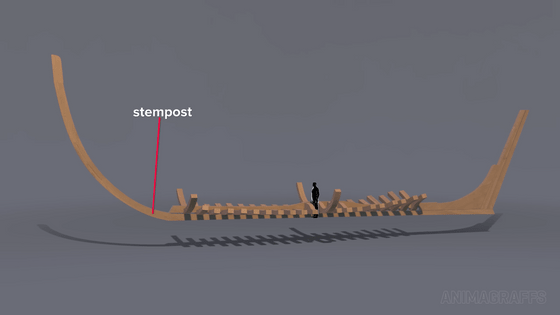

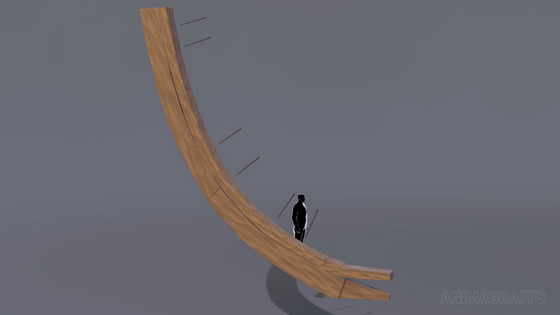

The construction of galleons, which were used from the mid-16th century to the 18th century, begins with the laying of the 'keel,' which runs along the entire bottom of the hull from bow to stern. After that, beams called floor boards are fixed to the keel, and another girder called the 'keelson' is placed on top.

Attach the bow and stern members to the structure.

Iron spikes and nails were used to fasten each part, and wooden spikes called 'tori nails' were also hammered into the ground.

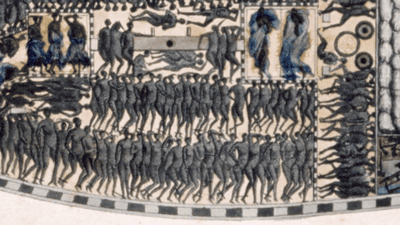

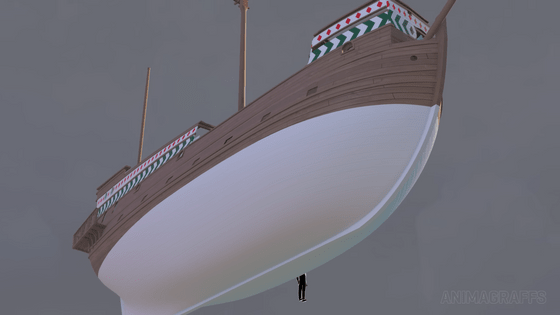

The discovered paintings reveal that the underwater parts of the ship that were in constant contact with seawater were covered with a white coating called 'white stuff' made from whale oil, fish oil, rosin, and sulfur for protection. However, the hull of the galleon was constantly exposed to attack by wood-eating marine creatures such as shipworms and barnacles. The hull of the galleon was also constructed with a 'tumblehome' structure that curved inward and narrowed towards the top.

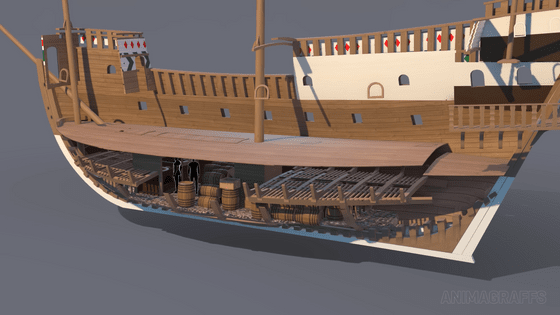

The ship's lowest compartment, the hold, contained over 100 tons of ballast to balance the weight above the waterline, as well as bread, biscuits, salted beef, cheese, butter, and beer.

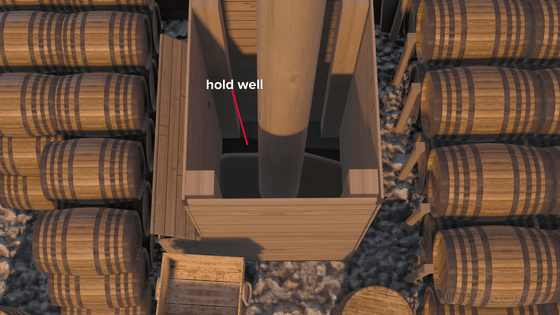

A well was also installed in the center of the hold to pump out any water that had accumulated in the bottom of the ship.

Additionally, there are lockers for storing shells and other items, based on the idea of 'keeping heavy objects as low on the ship as possible.'

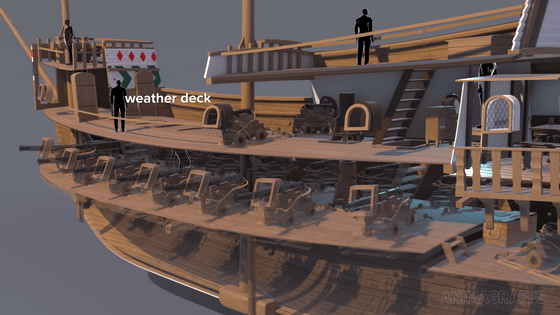

The deck above the waterline was called the 'orlop deck' and was used to store bread, gunpowder, lanterns, sails and timber.

The English galleon '

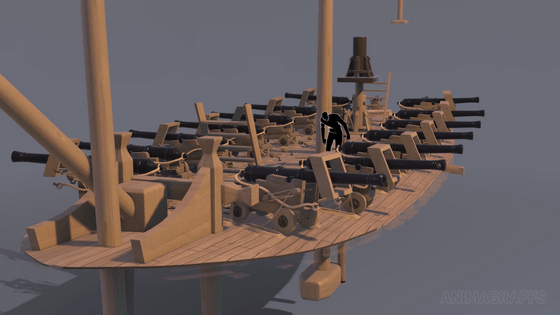

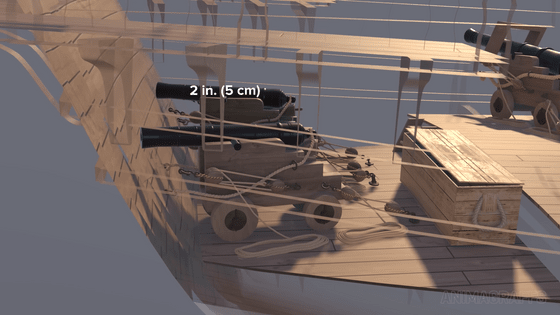

The stern of the ship was fitted with two

The 'weather deck' above the main deck was equipped with two cannons, as well as

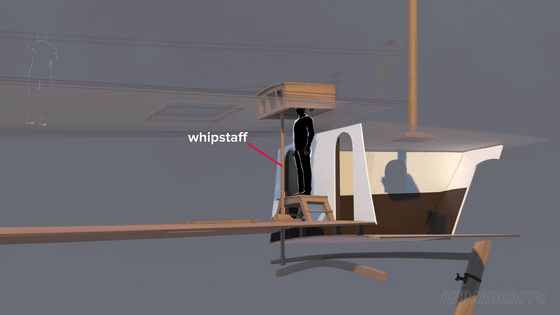

The helmsman also stood on a platform to check the situation outside and gave instructions to the crew on how to operate the whip rudder.

An additional swivel gun could be placed on the raised forecastle at the bow.

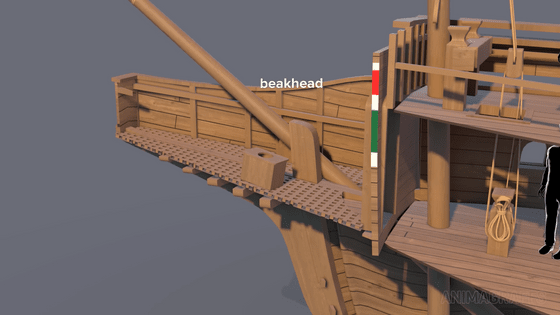

There was also a toilet installed at the bow of the boat.

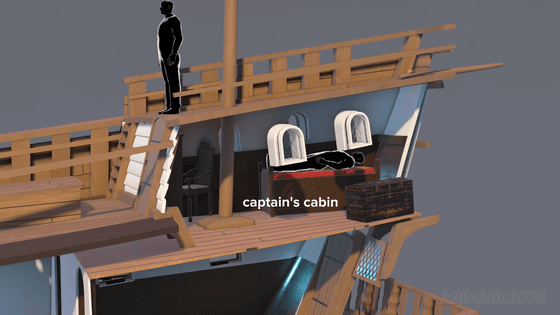

At the rear of the ship was a poop deck accessible by a ladder, and below the deck was the captain's quarters.

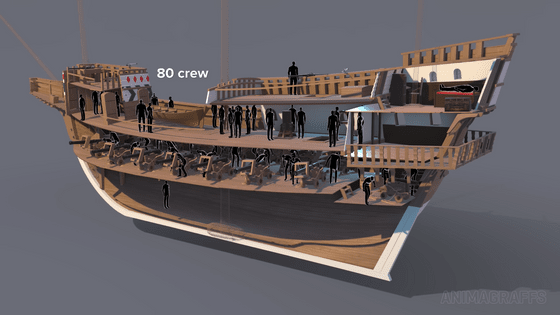

The Golden Hinde had a crew of about 80 people, who slept on mats laid out on the deck (hammocks only became common on sailing ships in the 17th century).

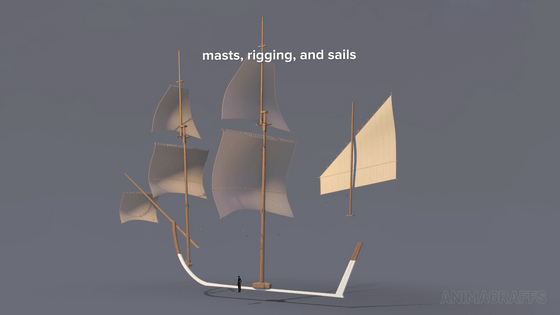

The masts attached to the hull can be up to 100m tall, with the front mast called the foremast, the middle mast called the main mast, and the rear mast called the mizzen mast. The two front masts generate propulsion, and the rear mizzen mast is used for balance and steering.

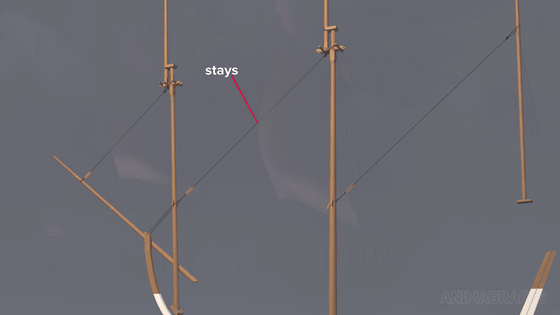

The mast was supported by ropes called shrouds and stays, which held the mast in place and prevented it from tipping over when the sails were hit by the wind.

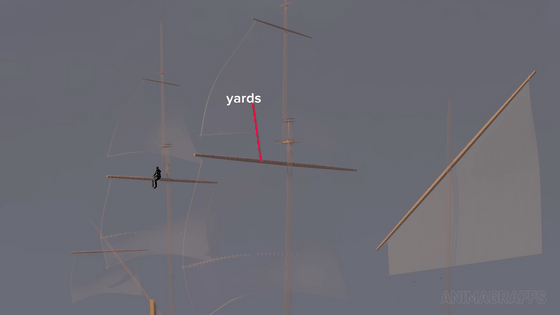

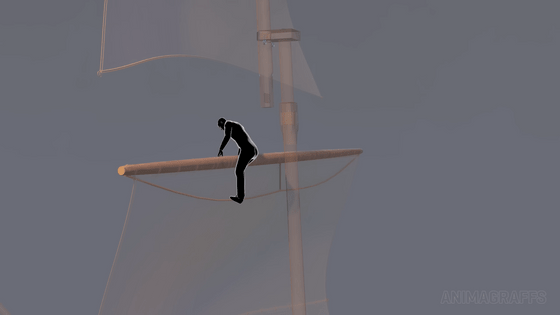

The sails are attached to horizontal pieces of wood called 'yards' and can be moved up and down using a system of ropes and pulleys.

Adjusting the sails is a complex task that requires adjusting the sails according to the wind, but the sailors were able to skillfully manipulate them to sail the ship upwind.

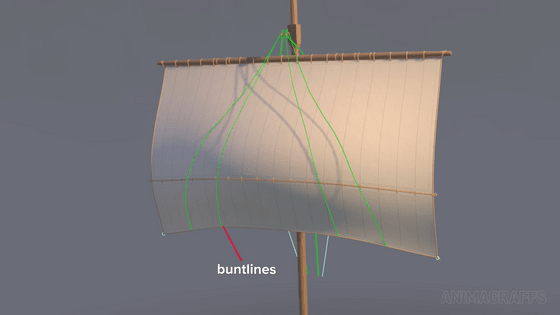

The sails were fitted with 'cleat lines' and 'bunt lines' to adjust their position up and down, as well as 'sheet lines' and 'tack lines' to adjust the angle of the bottom of the sail and control how open it is.

A rope called a 'martinet' controlled the sides of the sail and prevented it from being overfilled by the wind, while the 'bow line' kept the sail at the optimum angle to the wind.

Generally, ships are equipped with

Raising an anchor, which is now generally done electrically, used to be a complicated process requiring the cooperation of several crew members. First, the ship would approach the anchor with its bow facing it, and the crew would use a winch to reel in the anchor cable.

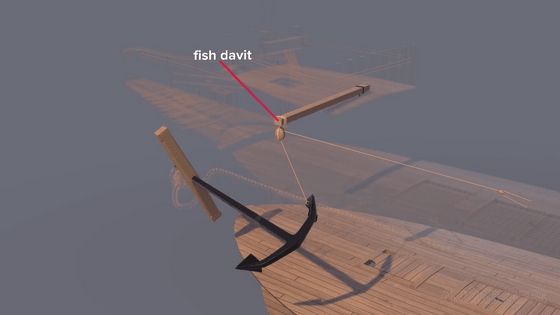

Next, when the marker board rises to the water surface, a cable is attached to the cathead at the bow and the anchor is pulled up further.

In addition, a cable is attached from the fish davit to the tip of the anchor, and the anchor is fixed sideways to the anchor bed on the side of the ship.

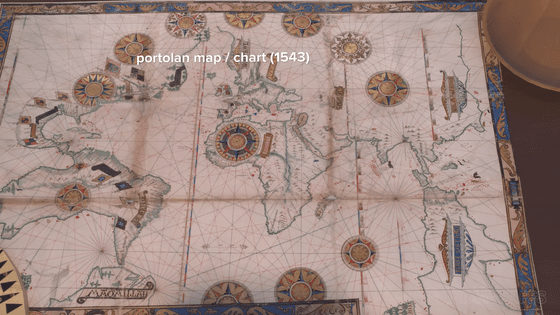

In the 16th century, before GPS was available, navigation required complex tasks using a variety of tools and techniques, including astronomical observations, dead reckoning, compasses, and hourglasses.

While it was relatively easy to determine latitude by measuring the altitude of the sun and stars, determining longitude was a very difficult task. Therefore, navigators used compasses and speedometers to measure the speed and direction of the ship and estimate the current position from the distance and direction traveled.

However, because ocean currents and winds can easily cause errors, they would sometimes have to use landmarks to correct their course when land was in sight. In this way, it was pointed out that 16th century navigation relied heavily on experience and intuition compared to today.

Nevertheless, the navigators of the time made full use of these technologies to navigate the vast oceans and explore new routes and new continents that had never been seen before.

Related Posts: