A doctor who saved the life of a boy infected with a brain-eating amoeba that has a nearly 100% fatality rate talks about the treatment process

Live Science, a science news site, interviewed the doctor who treated the boy infected with

This is what it's like to treat a 'brain-eating' amoeba infection | Live Science

https://www.livescience.com/health/this-is-what-its-like-to-treat-a-brain-eating-amoeba-infection

Naegleria fowleri lives in warm freshwater lakes, rivers, and hot springs, and if it enters the body through the nose with water, it invades the brain and causes primary amebic meningoencephalitis . Very few people survive this infection, and the mortality rate is said to be over 97%. In addition, the expansion of the habitat due to recent climate change is a problem .

Dennis Conrad, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas Health Science Center, is retired from the medical field at the time of writing, but in August 2013, when he was working at a hospital in San Antonio, Texas, an 8-year-old boy infected with Naegleria fowleri was rushed to the hospital. Below are the questions asked by Live Science during the interview and Conrad's answers.

Q:

What happened to the boy?

Conrad:

He spent summers with his mother in Mexico, where they lived in 'colonias,' sparsely populated settlements on the U.S. border and relied on natural water sources for bathing and laundry.

The child liked to swim in a tributary of the Rio Grande, so it is believed he contracted the infection while swimming in the river. One of the characteristics of the amoeba in question is that it feeds on bacteria such as E. coli, which means areas polluted by sewage are ideal places for the amoeba to multiply.

Q:

What was the child's condition when he was brought to the hospital?

Conrad:

His mental condition had deteriorated significantly, and although he responded to basic stimuli such as pain, he was not able to communicate with his environment. He had been examined at several clinics in Mexico, but initially presented with symptoms that could not be distinguished from viral or other illnesses - fever, headache, general malaise, loss of appetite - and was either not treated or given an antibiotic injection and sent home.

However, as his condition worsened, he began to experience symptoms such as increased intracranial pressure, vomiting, and drowsiness, and it was eventually discovered that he had a serious, progressive illness for which traditional outpatient treatments were ineffective.

After being examined at a medical facility on the border, he was referred to a hospital in San Antonio for serious illness, where he was found to have signs and symptoms of meningitis. During a cytology test, some people said they could see amoeba-like objects in his cerebrospinal fluid.

Q:

Why does a bacterium cause such meningitis?

Conrad:

The pathogen is a single-celled but complex organism that the body recognizes as not being one of its own, triggering an immune inflammatory response. Perhaps the main reason why patients present with such obvious symptoms is the host's profound inflammatory response to the pathogen. In the course of this response, neurons and other cells of the central nervous system are accidentally or collaterally damaged.

As a side note for further understanding, much of the damage caused by meningitis is not specific to amoebas:

Q:

What treatment did the child receive?

Conrad:

We treated him with a combination of drugs, which in

This was possibly the first case that could be treated with a drug called miltefosine , so I called Atlanta early in the morning to get permission from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to use it, because it's only approved for experimental use, and I think it was about 11 a.m. that day, I received the drug and started treatment.

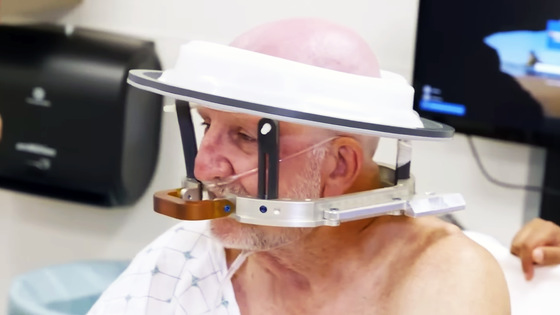

Ultimately, what helped him survive was the relief of the increased intracranial pressure caused by brain swelling and cerebral edema. Early in the morning, a brain surgeon was called in to insert third ventricular drainage devices into both sides of his head, which mechanically drain fluid from the spaces inside the brain called the ventricles, relieving the pressure.

The two children I treated in the past who died ultimately died from complications of cerebral edema. The cerebral edema eventually developed

About 36 hours after starting treatment, the amebas were no longer found in the ventricular fluid that was collected periodically from the drains. Because we were able to actually collect and test the fluid that was discharged from the body, we had evidence that the amebas had been killed.

But there were still dead cell proteins floating around in the brain, so I continued to fight the inflammatory response, and I think corticosteroids helped with that, because they reduce the swelling to some extent and also have an anti-inflammatory effect.

Q:

Because it is a very rare infection, it would seem difficult to detect, but is this actually the case?

Conrad:

If you have the right indicators and the right environment, I think you can diagnose it pretty early on, especially if you have experience like I did.

Q:

How long did it take for the boy to recover? How long did he stay in hospital?

Conrad:

I'm a consultant doctor so I lost contact with him after he left critical care, but I believe he was in hospital for around three weeks, after which he had to be looked after by skilled nurses and then in rehabilitation, because although he survived he never fully recovered from the damage caused by the inflammation that occurred before treatment started.

Q:

What general advice would you give to parents who are concerned about these infections?

Conrad:

It's best to avoid infection. Importantly, chlorinating your water is enough to kill the amoebas. A minimum of 10 ppm (10 mg per liter) of free chlorine should be sufficient, so if you swim in chlorinated water, there's no need to worry.

Also, since these creatures cannot tolerate high concentrations of salt, swimming in the sea is also a good idea. Reports from the United States show that there are many cases of infection in warm southern states. If you are going to swim in waters where amebas are present, it is wise to avoid diving and, if possible, refrain from putting your head in the water. This is because if water enters the nasal cavity, it will physically splash onto the cribriform plate (the bone at the roof of the nasal cavity), causing the amebas to move to the brain.

Be especially careful if you see warnings against swimming due to high E. coli levels, as the water is like a food court for amoebas.

One final thing to keep in mind is the speed of the water. Amoebas love stagnant water that is full of plant matter like leaves, so if you swim in a fast-flowing river, you don't need to worry about getting infected by amoebas.

Prevention is key with these types of infections, and ideally you would want to avoid the risk altogether, but if you are at risk, it's a good idea to be aware of where the risk is. However, this disease is rare in the United States, with an average of less than 10 cases per year, so parents with children should be concerned about other dangers.

Related Posts:

in Science, Posted by log1l_ks