The untold story of a Japanese submarine cable repair ship that began repairing undersea cables severed in the Great East Japan Earthquake immediately after the disaster

The invisible seafaring industry that keeps the internet afloat

https://www.theverge.com/c/24070570/internet-cables-undersea-deep-repair-ships

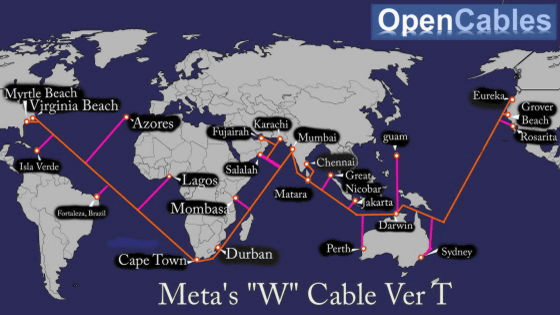

The world's internet traffic, including email, social media, bank transfers, and video streaming services, is carried by undersea cables as thin as a garden hose. The length of the undersea cables stretching across the bottom of the Earth's oceans is about 800,000 miles (about 1.28 million km), and it is said to consist of about 600 different systems.

Although the ends of the cables are buried near the coast, most people are unaware of their existence, as most of the cables connecting continents and islands lie deep under the sea. However, their importance is very high, because if all the undersea cables were cut, all functions of modern civilization, including financial systems, logistics, office work, and entertainment, would stop. Fortunately, the undersea cables that are spread all over the world have redundancy, so it is almost impossible for a well-connected country to lose all Internet connections at once.

Even so, undersea cables are cut about 200 times a year around the world, and each time they are cut, they must be quickly restored. There are about 20 undersea cable repair ships around the world, one of which is the Ocean Link, which was launched in 1991.

On the afternoon of March 11, 2011, just before the Great East Japan Earthquake, Ocean Link was carrying out repair work 20 miles (about 32 km) off the Pacific coast of Japan to address damage to the undersea cable connecting northern Ibaraki Prefecture and California in the United States. About two weeks after leaving Yokohama Port that day, the repair work was almost complete, and all that remained was to use the remotely operated unmanned submersible (ROV) 'Marcas' to re-bury the cable on the seabed.

At that moment, the ship was suddenly hit by a strong tremor that made it difficult to stand, and when they checked the television, they found that a huge earthquake had occurred 130 miles (about 210 km) northeast of the ship. Due to the risk of a tsunami, repair work was suspended and Ocean Link was temporarily evacuated until the tsunami subsided. After the tsunami passed, the crew learned about the damage in Japan from the television news, but the ship's satellite phone was not working.

In the midst of the chaos, Chief Engineer Mitsuyoshi Hirai, while worrying about his family in Kanagawa Prefecture, began to think that he would be busy repairing the undersea cables damaged by the earthquake. Large earthquakes often damage a large number of undersea cables at once, so in some cases, there is a possibility of a large-scale Internet outage occurring all at once. In fact, on the night of the 11th, Ocean Link received a series of messages informing them of cable failures.

During the Great East Japan Earthquake, telephone lines and mobile phone base stations were destroyed, so people communicated with each other through email and online services such as Skype. Therefore, many people may have had the impression that 'the Internet was fine even though the telephone was out of order,' but by the next morning, it was discovered that seven of Japan's 12 trans-Pacific cables had been cut, and Japan's Internet connection was in a rather critical situation.

Two days after the disaster, Ocean Link returned to Yokohama Port to prepare for the repair of the undersea cable. At the time, the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident had led to the risk of radioactive contamination in the waters off Japan, and no undersea cable repair ships were dispatched from the surrounding waters, so Ocean Link was forced to work alone. The crew obtained Geiger counters to measure radiation and were trained in how to use them.

Eight days after the port call, Ocean Link set sail again, heading for the work site 160 miles (about 257 km) south of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. This was one of the furthest fault lines from the nuclear power plant, but before work began, Hirai, wearing protective clothing, conducted a radiation test, and then periodically checked for radiation to ensure safety.

The basic methods for repairing undersea cables have remained largely unchanged since

In the fifth and final installation, a new undersea cable was laid across the Atlantic Ocean, and a sunken cable from a previous installation was raised and connected to another cable on board, making a total of two cables successfully laid. The method of raising the sunken undersea cable was an analog method of hooking the cable to an anchor that was dragged along the ocean floor and then raising it up.

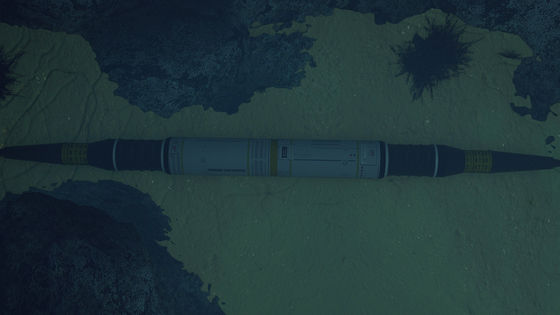

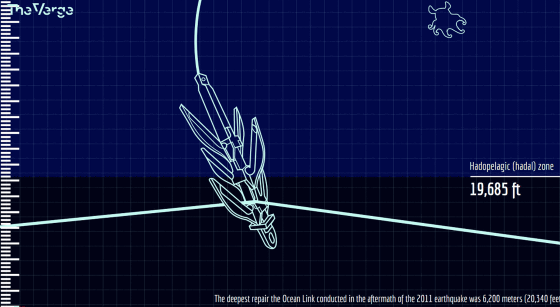

Modern cable repair ships, including Ocean Link, use high-tech equipment, but they still basically use the same methods to pull up cables as in the 19th century. Submersibles like Marcas are useful in relatively shallow waters, but in harsh environments where the ocean floor can reach depths of several thousand meters, the most stable method is to hook the cable onto a hook that is dragged along the ocean floor. The deepest cable repaired by Ocean Link during the Great East Japan Earthquake was 6,200 meters deep.

When the Ocean Link arrived in the planned area on March 22, it took more than six hours to lower a hook, which is suitable for dragging the rocky seabed, to the seabed more than three miles deep (about 4,600 m). Then, the Ocean Link slowly moved forward, and Hirai and other engineers kept a close eye on the tension meter on the anchor, waiting for the undersea cable to get caught.

The next morning at 6am, the undersea cable was caught and reeling began. It was fortunate that the undersea cable was caught on the first advance, but Mr. Hirai judged that the cable was highly likely to have been buried under debris from an undersea avalanche due to the high tension, so the cable was reeled in at a very slow speed of 10 feet (about 3m) per minute to avoid breaking. As a result, it took 19 hours after the start to reel in the cable. Moreover, the undersea cable was damaged in a way that even Mr. Hirai, a veteran, had never seen before, and there was a risk that the cable connecting the seabed to the ship would break, leading to a major accident, so the work was carried out very carefully.

In repairing a submarine cable, first one end of the cable is pulled up onto a ship and secured to a buoy or other marker and returned to the seabed, then the other end is pulled up, the cut section is cleaned up, and connected to a spare cable. The other end connected to the buoy is then pulled up and connected to the other side of the spare cable, connecting the two broken cables together. In the final stage, the two cables extending from the seabed are connected to the ship, making them particularly vulnerable to the effects of wind and waves.

Despite the difficulties of getting tangled in fishing gear, repeated radiation inspections, and storms, Ocean Link completed the first repairs in a month. After that, they completed other difficult tasks, such as replacing a group of submarine cables that had been damaged by a landslide with a new system with new branching units, and finally returned to Yokohama Port in August. The final task was repairing the submarine cables that had been suspended due to the earthquake on March 11. After coming ashore and writing his final daily report, Hirai said he realized his work was done when he saw other passengers using their mobile phones on the train back to Yokosuka.

Submarine cable repair ships have saved the world from internet connection crises many times, not just after the Great East Japan Earthquake, but they are not well known given their importance. Although major technology companies announce new submarine cable laying plans almost every year, there is a lack of investment in maintaining them, and the aging of repair ships and a lack of successors are becoming problems.

In fact, in 2023, all five undersea cables connecting Vietnam experienced problems, and delays in restoration work had a long-term negative impact on Internet connections. The cable damage was not caused by a catastrophic event such as an earthquake, but rather sporadic damage caused by fishing, shipping and technical issues, but nearby repair ships were busy with other repair work and were unable to attend to the repairs.

The Verge points out that people are only focused on laying submarine cables and not so much on maintenance. In addition to a lack of investment in building and maintaining submarine cable repair ships, they claim that training successors with specialized skills is a major challenge. 'The bigger threat to the long-term survival of this industry is that people are aging, as are the ships. It's a profession where you learn most things on the job, so training talent takes longer than building ships,' The Verge said.

Related Posts:

in Web Service, Vehicle, Posted by log1h_ik