John Romero, the creator of the FPS monumental 'DOOM', talks about 'What was the development of indie games in the 1990s like?'

The FPS game ' DOOM ' developed by id Software is a game that had a great influence on the FPS genre, and is still popular with people even 20 years after its release. An interview was conducted with John Romero , a game designer who led id Software, about how it was thought at the time to release a game by an independent company like DOOM.

John Romero on his book Doom Guy and developing games at a small scale – How To Market A Game

https://howtomarketagame.com/2023/09/25/john-romero-on-his-book-doom-guy-and-developing-games-at-a-small-scale/

In the early 1990s, Mr. Romero worked full time for the software company Softdisk . Softdisk is known as a company that provided a monthly subscription service called ``Gamer's Edge'' that ships floppy disks filled with PC games every month.

Mr. Romero's team innovated technology to make PC games horizontally scroll as smoothly as on the Family Computer, and founded id Software to release games that utilize this new technology. Games made with id Software were published by Apogee . When Mr. Romero left Softdisk, Softdisk's CEO realized the amount of talent he was losing and negotiated with id Software, which ended up making six more games for Softdisk in 1991. There is also an episode that has been told. Romero's team released a total of 27 games in 1990 and 1991.

Interviewer Chris Zukowski (hereinafter referred to as Zukowski):

Why did they make so many games in 1990 and 1991?

Mr. John Romero (hereinafter referred to as Romero):

When I worked for Gamer's Edge, we had to ship one game every two months. Only 6 in one year. But we also wanted to make more of the `` Commander Keen (game) '' series. So John Carmack and I spent almost all of our non-work time developing games, and in 1991 alone we created 13 games. I was really busy.

Zukowski:

How did you do it so quickly?

Romero:

Because our team of four has been making games together every day for 10 years. In particular, I had a lot of experience making small games, and I knew how many levels (surfaces) I needed to design.

Zukowski:

How did you decide on the level?

Romero:

Our first game, Slordax , dictated how many levels you could create and how long it would take to create them. At the time, I had no idea how much time it would take to create textures, characters, sound effects, and other things. You have to create a level and write an editor for it. We first determined our capabilities by seeing how many levels we could create.

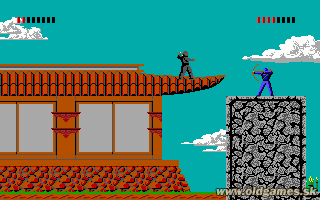

The second game, Shadow Knights , was a side-scrolling ninja game that was completely different from the first. I started making this as well, aiming to complete it in two months, and was able to grasp how many levels I could make. This is where we found ourselves speeding up.

At the same time as the second game, we were also working on Commander Keen, and we set a goal of completing 48 levels in all games in three months.

Zukowski:

In order to produce it that quickly, it was necessary to organize the ideas into smaller pieces. How did you do it?

Romero:

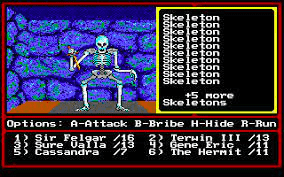

I had previously made large-scale games such as Might and Magic II: Gates to Another World . It was really fun to make, but it was too big for me to make by myself. Using this experience, we decided not to create a game that exceeded the amount of time we had.

I knew there were constraints and I knew those constraints were finite. So we didn't whine or complain because we couldn't make a big game. By maintaining this attitude, we were able to finish our obligation to contribute to Softdisk and create 100% pure, made-in-id Software.

Zukowski:

Weren't all games small back then?

Romero:

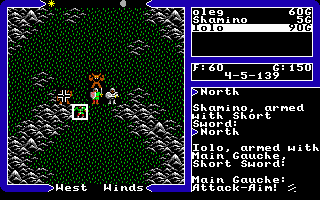

There was a big game in the 80's. For example, when it comes to `` Ultima V ,'' a team of about 10 people worked on it over several years. I think they programmed it in assembly language and compressed the large amount of data as much as possible to fit on maybe 10 disks. These projects were large-scale. I guess they had a producer on their team to handle all the tasks.

Zukowski:

There were many sequels to Commander Keene in a short period of time. Were you not worried about them cannibalizing each other?

Romero:

no. Because people wanted more.

Zukowski:

You guys released the first smooth 3D scrolling game with a game called Hovertank , but you released it through Gamer's Edge, not id Software, right? Why did another company release such a revolutionary hand?

Romero:

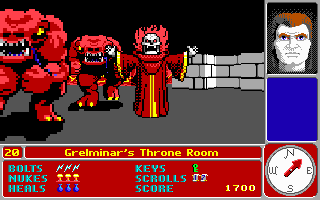

We were basically getting paid for experimentation and R&D and building the 3D engine. We built Hovertank, pitched it to Gamers Edge, and six months later we got the opportunity to do our first texture mapping on Catacomb 3D . Creating a 3D game was an experiment using Gamer's Edge funds.

The subsequent release, Wolfenstein 3D , was completely independent. I had made two 3D games before, so I knew how to do it. I didn't have to worry about funding because I had money from the Commander Keene series.

Zukowski:

When were you ready to move away from Commander Keene and make Wolfenstein and DOOM?

Romero:

I thought 3D was the way of the future, and I even thought that the time I spent on Commander Keene was a waste of time. This 2D is not possible and we need to break away from 2D. Thinking about this, I suddenly said this at 1am. 'We have this cool technology, but we're not using it,' he said. Then everyone immediately answered, 'Yes, you're right.' It is no exaggeration to say that this episode was the catalyst for the birth of Wolfenstein.

Wolfenstein was the first time we'd made a game that didn't have time constraints, so we thought, let's make a really good game and pack in everything we think we need. As a result, it took four months to release the shareware version. It took me a month and a half to complete the five episodes of maps and bosses, making it a total of five and a half months, including the hints and other things. However, it felt really good. I wasn't bound by time either. I think we were able to create a truly wonderful game.

Zukowski:

In the early days of id Software, you were probably making a decent amount of money, but probably not as much as the major studios. What do you think about that? Do you know how much money major studios made in the 1990s?

Romero:

When I worked at Origin Systems , I once heard about sales at a company meeting. In 1987, there was a profit of 3 million dollars (approximately 7.6 million dollars = approximately 113 million yen in 2023 value conversion).

I wanted to make a game that had the quality of something like LucasArts or Origin Systems, but at the scale that we felt was appropriate. I don't want to create a grand story. I just wanted to have a really fun experience.

Zukowski:

At that time, Softdisk only paid $5,000 ($11,405 = approximately 1.7 million yen in 2023 value) for each game you developed. Did you feel it was low compared to Origin Systems' income?

Romero:

No, I was rather surprised at how much it was. At that time, rent was really cheap so it wasn't a problem. It was a few hundred dollars a month. Our goal was to survive as a company and as a team. When we got our first check and decided to start a company and work full time, we were just four people. Our first thought was, 'We need to keep as much money as possible in the company.' At that point, each person's financial situation, such as rent and bills, was different for each person. Some may have had car loans.

After that, we started making $50,000 a month, and we got small raises, but we kept as much as we could in the bank. Even if the game didn't sell well, there was a recession, or it took too long to make the game, there was still a need to complete the game and release it to the world. So I had to be as conservative as possible. Yes, we didn't buy anything. I was just working.

Zukowski:

Nowadays, sales in the first month have a huge impact on a game's revenue. What was the revenue curve for newly released games in the 1990s?

Romero:

Because the number of people who were exposed to the game was limited, it continued to sell steadily for a very long time. The number of people who could play the game was limited. In the early years, sales continued to be high, peaking for at least half a year, and then declining. At that time, accumulating income was important. I needed to earn money from multiple games at the same time.

Zukowski:

How did you make money after Wolfenstein and DOOM became big hits?

Romero:

After DOOM, it was around the time I started working on

Zukowski:

If you brought a 20-year-old John Romero to 2023, do you think he could recreate his 1990s productivity with today's tools and gaming environment?

Romero:

I think so. If you go to itch.io or other indie gathering places, you can enjoy a wide variety of indie game art styles and games.

Horror games are hugely popular in indies, and they also have a graphical aesthetic reminiscent of the 1995 PlayStation. Creating graphics of this quality takes less time than using Unreal Engine, which pursues realism. Now that the engine is complete, we can spend as much time as possible on the gameplay part. This aesthetic is very important.

Zukowski:

If I were a game developer and I told you that my ideal game was Final Fantasy, what would you think?

by CLF

Romero:

We need to thoroughly narrow down the scope of what we can do. Having an idea of scale is perhaps the most important thing you can do in the early stages of development. If we narrow it down to the horror genre, what horror games have left the most impression on people over the past few years? I think it's ' PT '. It's that hallway. Everyone will remember, right? This game speaks perfectly about the amount of content you need to stay in people's minds, it's the design that matters, not the scale, it's not a huge adventure, it's your chosen genre, and no one will ever watch it. It teaches me that doing something completely new and never done before is truly unique.

If you're going to spend a lot of time on the game, you should spend it on the design. You should really think about what you're doing and come up with new things that push the boundaries of the genre.

Zukowski:

What if you're stuck in development hell for two, three, or four years?

Romero:

If you don't see an end in sight, if you don't know where you're going, but you have another idea that's more exciting, this is really hard advice, but no matter how much time it takes, do what you want to do the most. I would like you to do something.

Try to make something more viable in a shorter span of time. Even if your success is modest, you will have learned something. Next, let's do something a little bigger. It can be a sequel, it can be a side story, or if it's the type of game you like, you can always start small, release something interesting, and work your way up from there.

However, the greater the deviation, the more you will deviate from the course. Think about your career path many years from now. If there is one degree of deviation, what will happen in a few years? Misalignment will grow over time, so you need to make good decisions right from the start and correct them as soon as possible. If you think something is wrong, cut your losses as soon as possible. Time is limited. The number of matches is limited.

Related Posts:

in Game, Posted by log1p_kr