A record that approaches the mystery of a pedestrian bridge erected in an almost empty place

There are few official records of the pedestrian bridge located in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA, as to when it was built, by whom, and for what purpose. Blogger Tyler Vigen, who often passes by the area and suddenly became curious about the existence of the pedestrian bridge, solved the mystery of why the pedestrian bridge was built and published his report.

The Mystery of the Bloomfield Bridge

Just west of the Minneapolis Airport, there is a pedestrian bridge that spans Interstate 494 (I-494) and connects the cities of Bloomington and Litchfield. There is a fast food restaurant Taco Bell on the north side of the pedestrian bridge, and a warehouse for an industrial goods store called Grainger on the south side, but it seems that this pedestrian bridge is rarely used.

Mr. Vigen said he often drives on roads under pedestrian bridges, but he wondered about the existence of pedestrian bridges that are neither located in particularly easy-to-walk areas nor do they connect facilities that clearly need to be connected. . One day, after leaving Taco Bell and arriving at the foot of the pedestrian bridge, Vigen noticed another oddity about the bridge: the north end of the bridge connected to a green space beside the road rather than a sidewalk. 'Why isn't there a sidewalk? It doesn't make sense!' thought Vigen, so he decided to start a thorough investigation into pedestrian bridges.

When Mr. Vigen asked the people at Grainger about the pedestrian bridge, he said, ``I don't like it because neither employees nor customers use it, and there's trash accumulating at the edge.'' The employee also said, ``I don't eat at the Taco Bell over there. There's a better Mexican restaurant nearby.'' This suggests that not only local residents but also the people at the shops who would use the pedestrian bridge the most would have to use the pedestrian bridge. It turns out that I was ignoring the existence of

Mr. Vigen then searched the Internet for the number written on the bridge girder. There was a plate on the pedestrian bridge that read 'Federal Aid Project FAI 494-4-32 Minnesota 1959,' so Mr. Vigen first searched for 'Federal Aid Project 494-4-32,' but found nothing. I was told that there wasn't. Although there was a website for records of federally subsidized projects, the earliest records I could find were from 1992.

'I never expected to learn so much from such a bold plate,' Vigen said. Since he could not find detailed information in other words, Mr. Vigen next looked at photos from the time of construction and proceeded with his investigation.

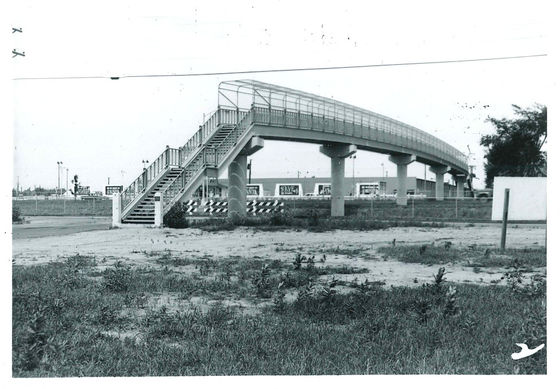

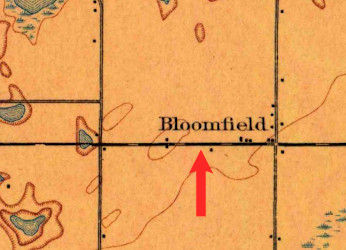

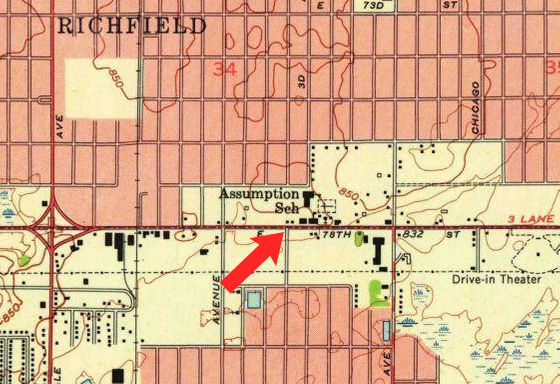

An aerial photograph thought to have been taken at the time of construction (1959). The pedestrian bridge in question is indicated by a red arrow, and you can see that at that time there was nothing but a field at the southern end.

Naturally, the question that arises is, 'Why build a pedestrian bridge on empty land?' It is true that there is a residential area on the south side of the field, but if you are in that residential area, you should be able to use the two sidewalks a little further east or west. If pedestrian bridges were not built for residential areas, what were they built for?

Vigen looked it up on the internet and found an organization called the I-494 Bridge Committee. This committee is a group made up of residents of cities along I-494, and its purpose was to encourage people to avoid driving as much as possible in order to relieve the severe traffic congestion on I-494.

Mr. Vigen sends a message to the commission's executive director, Melissa Madison, explaining that he is looking into the pedestrian bridge and asking if she could provide any information about why it was built. .

Mr. Madison responded immediately and was willing to make time for me. Melissa didn't know why the pedestrian bridge was there, but she said she contacted city and state officials several times to see what information she could get.

Madison contacted Bloomington's planning manager, Glenn Markegaard, who also didn't know why the pedestrian bridge was there. However, Markegaard points out, ``It was probably built in anticipation of future development.'' Much of the infrastructure at the time was built in anticipation of future growth, and the existence of vacant lots supports this theory. He said that it seems that there are.

So Vigen decided to dig deeper into this theory. According to Vigen, 1959 was the heyday of interstate highway construction. In 1956, President Eisenhower decided that there were too many bumps in the road to California and signed the Federal Highway Act, which resulted in the federal government funding 90% of the construction costs for interstate highways. , road maintenance began to be actively carried out.

The speed of interstate construction was a hot political topic at the time, and politicians with deep pockets had to launch labor programs to create jobs for people. When you combine the high growth rates of Bloomington and Litchfield at the time and the prospects for future development, it's no surprise that politicians would decide to build a pedestrian bridge. This has led to the hypothesis that ``the pedestrian bridge was constructed to generate public works projects, and that there was no specific reason for it.''

However, the question remains, 'Even if there was no reason, why was it built in that location?' Mr. Vigen, who thought, ``There must be a reason why the pedestrian bridge was built in that place,'' conducted further investigation.

When Mr. Vigen discussed this issue with many people, he said, ``Isn't there a law that requires pedestrian bridges to be built at regular intervals?'' The 1960s was the age of the automobile, but cyclists were vocal in their advocacy for road improvements, so it was no surprise that there was a law requiring pedestrian bridges to be built for bicycles.

However, it turns out that no such law existed. In addition, there are many interstate highways without pedestrian bridges, and even if you narrow it down to Route 494, only one other highway was built around the same time as the pedestrian bridge in question. This refutes the theory that it was stipulated by law.

However, even if there were no law stating that bridges must be built, there would have been at least some discretionary authority over where bridges should be built. Vigen investigated this and wrote a letter to the Minnesota Department of Transportation's Bridge Division, which manages the highway.

Mr. Peter Wilson of the Bridge Division responded immediately and provided us with the original blueprints for the pedestrian bridge and a photo of the pedestrian bridge taken immediately after construction. The blueprints thoroughly described how the pedestrian bridge was constructed and listed the names of many of the people and companies involved in its construction. However, it was not explained why the pedestrian bridge was built here.

Photo taken at the time of construction.

Photo as of 2023. The appearance of the pedestrian bridge has not changed much.

A monochrome photo taken directly in front of the pedestrian bridge. On the other side of the pedestrian bridge, you will see a sign and a building that says 'Atlantic Mills Thrift Center.' It is also possible that this thrift center, or thrift store, lobbied for the construction of the pedestrian bridge.

Unfortunately, all the people involved in the construction of the pedestrian bridge in 1959 had already passed away. Mr. Vigen's grandmother remembers Atlantic Mills, but all she remembers is that ``they were having a really good sale.''

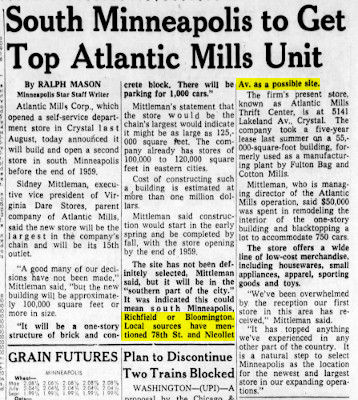

Mr. Vigen's next destination was an old newspaper. Mr. Vigen previously searched for ``494,'' ``78th street (name of the street near the pedestrian bridge),'' ``pedestrian bridge,'' etc. on the newspaper archive service, but he did not obtain very useful results. However, a search for 'Atlantic Mills' yielded a hit, and an article was published about Atlantic Mills being planned for construction in 1959, the very year the pedestrian bridge was built.

In a newspaper clipping with the headline 'Atlantic Mills to come to South Minneapolis,' the section highlighted in yellow reads, 'Suggested locations are Bloomington or Litchfield at 78th Street and Nicollet.'

According to the article, as of February 1959, the location had not yet been determined. On the other hand, documents obtained from the Minnesota Department of Transportation stated that ``a site survey for construction had been completed in October 1955.'' This indicates that planning for the pedestrian bridge began at least three years before the location of Atlantic Mills was decided, so it is unlikely that Atlantic Mills influenced the location of the pedestrian bridge, but rather that the pedestrian bridge was built. It is more natural to think that Atlantic Mills was built from

Mr. Vigen, who had exhausted all available clues at this point, decided to review aerial photographs and maps from the 1800s to the 1900s. After flipping through some of them, I found two interesting points.

First, we learned that the area where the pedestrian bridge was built was once called 'Broomfield.'

The area labeled 'Bloomfield' on the map was the area between present-day 'Bloomington' and 'Litchfield.' However, although the place name 'Bloomfield' was recorded on maps from the late 1800s to the 1950s, it eventually disappeared.

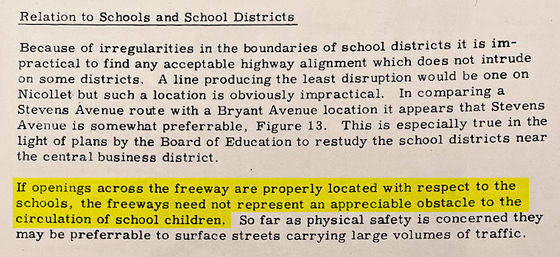

Another 1954 map created by the U.S. Department of the Interior had the word 'Assumption Sch.' prominently written just north of where the pedestrian bridge would be built. This was a big clue, and if there was a school here, it would have been the best reason to build a pedestrian bridge.

Assumption School remains in its form as Assumption Church at the time of writing this article.

The church was hidden behind a grove of trees from the interstate, and Vigen didn't notice it.

The Assumption Church website has a page about 'History'. According to this, the church was built in the 1800s, and in the 1900s it also served as a school and developed together with the local community, and at its peak from 1959 to 1961, as many as 1,170 students attended.

'What a discovery!' said Vigen. He contacted the church and asked, ``If you knew anyone who lived in this area in the 1950s or 1960s and would like to talk to me, could you please pass on my contact information?'' Ta.

The next day, I received a call from a woman who introduced herself as Ann Anton. Mr Anton, 75, was born in 1948 and said he moved to Litchfield with his family in the 1950s and still lives there. Mr. Anton attended Assumption school from 6th to 8th grade (equivalent to 6th grade to 2nd grade in junior high school in Japan), and although he did not have to use the pedestrian bridge himself, children living on the other side of the road He said he often saw them using the pedestrian bridge.

'The church was the center of social activity in the area,' Anton said, confirming the literature that Assumption Church was a pillar of the community's growth in the 1950s and 1960s, drawing hundreds of local residents. Looking back, he said that he even built a building to serve as an activity base.

Mr. Anton's 99-year-old mother used to be the principal of Assumption School, but she doesn't remember anything about the pedestrian bridge. Mr. Anton didn't know why it was built, but he believed it was definitely for use as a route to school.

Although Mr. Anton's story is strong evidence to support the theory of a pedestrian bridge to school, it is still not solid evidence. Mr. Vigen continued to investigate.

The next thing Mr. Vigen looked into was a report by George Burton titled ``Minneapolis Freeway'' that described the history of that time. Mr. Burton was commissioned by Minneapolis to study where interstate highways should be built. 'The road will not be an obstacle to commuting to school.'

This was the strongest evidence yet that pedestrian bridges near schools may have been built for students.

Vigen then asks the history center's staff to pull out any records related to interstate projects, federal aid projects, or the Minnesota Department of Highways that could be related to I-494 and the construction of the pedestrian bridge. . After reviewing those materials, the record that seemed most useful was a history report written by Howard Cairo, a 9th grade student at the time (equivalent to 3rd grade in junior high school).

This report written by Mr. Cairo was written as a school assignment, but for some reason it ended up in the archives of the historical society. In her report, Ms. Cairo provided some answers to Mr. Vigen's questions.

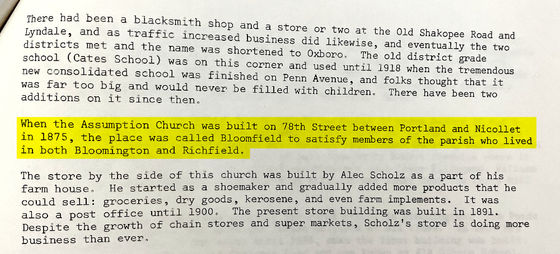

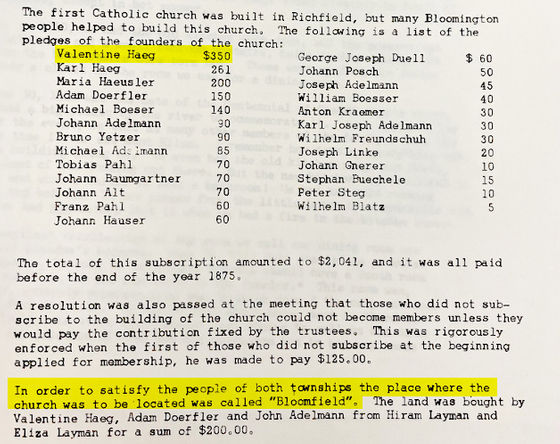

According to the report, when Assumption Church was built in 1875, the site became known as 'Bloomfield' to satisfy both parish members who lived in Bloomington and Litchfield.

It was because of the church that the area became known as Bloomfield, and the name Bloomfield reflected the close ties between Bloomington and Litchfield.

'It may sound silly, but at the time the church was built, there was a close community connection on both sides of the interstate, and they purposely linked the city names to show that connection,' Vigen said. What better way to demonstrate that connection than by building a pedestrian bridge on the former Broomfield site to reconnect the community?'

Ms. Cairo did not properly cite sources for her report, so Vigen looked for other primary sources to support Ms. Cairo's claims.

Documents documenting the history of the Assumption Church found by Mr. Vigen include a study in Bloomington, where Hegg lived, and Rich, who built the church, in honor of Valentine Hegg, who donated more than anyone else to its founding. It was written that the place name was given as Bloomfield, which is a combination of the words Field.

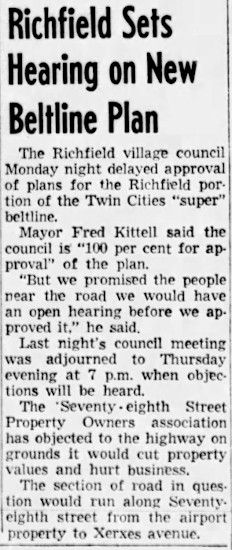

Additionally, a historical document titled 'Minnesota's Greatest Generation - Minnesota Historical Society' reveals that I-494 was known by local residents as the 'Beltline.' A search for ``Beltline'' turned up information that had not been found before, and they apparently succeeded in discovering an article from the local paper, the Minneapolis Star, that mentioned ``community hearings on plans for the Super Beltline.''

Although the article was published in 1955, there was no new information obtained from the article. So Mr. Vigen asked the city council if there were any minutes, but luckily it turned out that the minutes from 1955 still existed. However, it only stated that ``the discussion continued'' and did not provide any useful information.

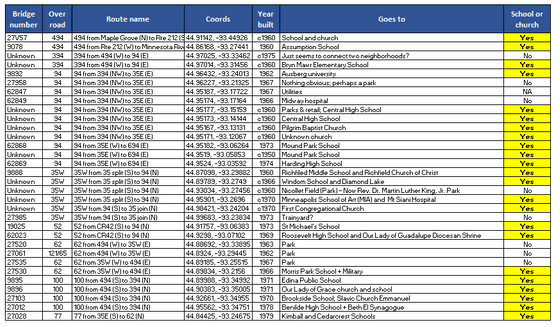

The next approach that Mr. Vigen took was to ``investigate other pedestrian bridges''. I thought that if I looked at other pedestrian bridges, I would be able to understand why they were built in this area.

When Mr. Vigen manually investigated all the pedestrian bridges on the approximately 500 km expressway, he found a total of 31 pedestrian bridges, of which 23 (74%) were connected to associations or schools. Most of the pedestrian bridges that didn't connect to churches or schools connected to parks or hospitals, and only two seemed to simply connect neighborhoods.

Mr. Vigen, who had been running around a lot, was about to publish the results of the survey, thinking that he would not be able to achieve any better results, when he happened to have an opportunity to talk to a colleague involved in public works management.

Janelle Foard, the city of Denver's chief operating officer who manages infrastructure, saw Vigen's photo and said, ``Stop looking at old documents. No one writes the real reason for an infrastructure project.'' 'You should first look for someone in power,' he said. If they wanted to prove Mr. Vigen's theory, he advised them to look for people who were connected to both the church and the footbridge.

So when Mr. Vigen made a list of powerful people, Fred Kittel, who was the mayor of Litchfield at the time the pedestrian bridge was being planned, caught his eye. This person had previously appeared in the minutes, which simply said 'discussion continued.'

Mr. Vigen, who searched by first name, found an article from the Minneapolis Star published in 1955 that read ``Litchfield offers freeway conditions.'' In it, Mayor Kittel talked about the interstate highway plan, and there was a line in it that said, ``There should be a pedestrian bridge on Second Avenue leading to Assumption School and Church.''

When Mr. Vigen read this, his first thought was, 'Oh my god! This is it!' The sentence ``Build a pedestrian bridge leading to the school on Second Avenue'' was exactly the basis for building a pedestrian bridge that Mr. Vigen was looking for.

By the way, the second thing I thought was, 'Wait, couldn't I have solved this mystery while sitting on the couch? There was no need to jump around.'

'If you ever have a debate about, 'Should I hire an expert sooner?' I'll point you to this anecdote. If I had consulted a colleague first, I could have saved two months,' Vigen said. ``At least now we have a complete answer to the mystery of the Broomfield pedestrian bridge,'' they wrote. He concluded with the sentence, 'Yes.'

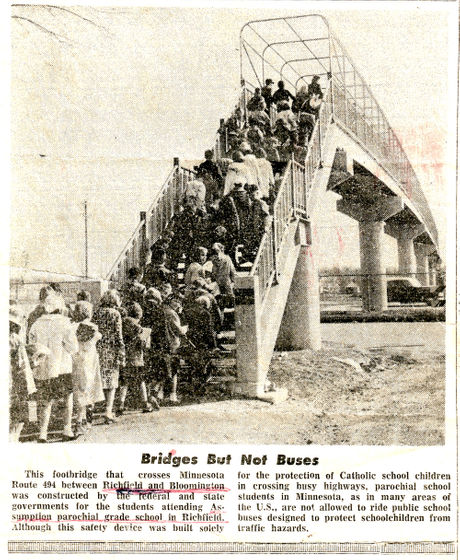

After this report was published, many local residents shared their memories of the past. Among them were photos of children using the pedestrian bridge.

Related Posts:

in Posted by log1p_kr