What is a specialist who can detect fraudulent treatises that reuse and process images with the naked eye?

Science publishing is already an industry with billions of dollars (hundreds of billions of yen), but in recent years research misconduct such as forgery of paper data has become a problem, and it is a challenge to ensure the validity of science. It has become. Meanwhile, American microbiologist

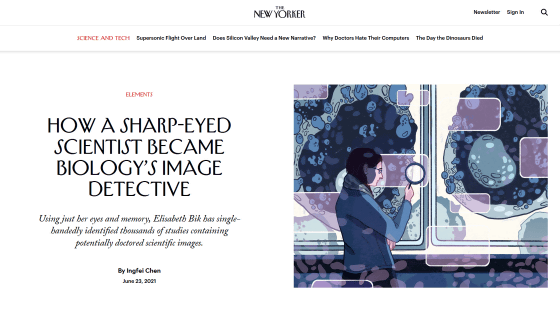

How a Sharp-Eyed Scientist Became Biology's Image Detective | The New Yorker

https://www.newyorker.com/science/elements/how-a-sharp-eyed-scientist-became-biologys-image-detective

In June 2013, Bik, a researcher at Stanford University at the time, read an article about fraudulent scientific treatises and wondered if his dissertation was plagiarized by someone. So when I copied sentences from my scientific paper and searched on Google Scholar, I found that some sentences were plagiarized by multiple online books without my permission. And this time, when I extracted the sentences from the book that plagiarized my paper and searched with Google Scholar, it seems that multiple papers that seemed to be the source of the theft were hit.

In the wake of this, Biku's hobby was to search Google Scholar for plagiarism during his off-hours, and he soon discovered as many as 30 fraudulent biomedical treatises. It seems that some of the papers were published in popular academic journals, and when Mr. Biku sent an e-mail to the editor of the publisher, some papers were withdrawn within a few months.

Then, in January 2014, when he saw an image of a technique called Western blotting that uses antibodies to detect proteins in a paper, Mr. Biku said that the inverted image was 'the result of another experiment' in the paper. I found it being reused. Although image defects do not necessarily invalidate the overall research results, images in scientific papers are evidence to support the author's findings, and image duplication and processing is a major problem.

Therefore, Mr. Biku investigated a new research published in PLOS ONE , an open access peer-reviewed academic journal, using the method of 'focusing on the images used without reading the text.' After investigating 100 studies in a few hours, Mr. Biku discovered that some images were used in duplicate, and it became a daily routine to search for illegal image use in the treatise. That's right.

Among the treatises that Mr. Biku discovered at PLOS ONE, there were duplicate patterns and copies of cell / tissue images, all of which had passed peer review. It seems that some of them simply mistakenly pasted the image from the file where a huge number of images are saved, but some of them were obviously processed for forgery purposes such as enlarging, rotating, and flipping the image. Some of them were done.

Initially, Bik didn't want to denounce other scientists fraudulently, and sent an email to a separate journal to point out the problem. However, since some academic journals have not been heard since they replied that they promised to investigate, they decided to express their concerns on the website PubPeer, where researchers ask and answer questions about the treatise. Bik uploaded a screenshot of the offending image, showing the important areas in blue or red boxes so that anyone can verify the similarities in the image.

Biku has discovered a large number of treatise frauds over the past few years, earning money from consulting, lectures and crowdfunding. In 2016, he collaborated with Ferric Fang and Arturo Casadevall, who were also studying dissertation fraud, to publish research results on the use of inappropriate images, and in 2019 he retired from Stanford University and `` Science Integrity. We have launched a website called ' Digest'.

When discovering problems with images used in treatises, general researchers rely on Photoshop to enlarge, invert, and overlay images, but Biku can do the same with just 'my eyes and memory.' That is. Bik says it only takes a few minutes to investigate the images contained in one paper, and in a 2016 study screened 20,621 papers and 782 papers 'inappropriate image duplication.' I pointed out. Of the 782 cases, one-third may have been just a mistake in pasting the image, but half were clearly processed. 'It can seem magical for the brain to be able to do this,' Fang said of Biku's abilities.

The research team reported to the editors of academic journals about 782 problematic papers, but as of June 2021, 225 were revised and tagged as 'Expression of Concern'. It seems that 12 cases were withdrawn and 89 cases were withdrawn, and more than half are still open to the public. Also, apart from this research, only 15% of the 4132 treatises that Mr. Biku has reported so far were dealt with at the time of writing the article. On the other hand, Bik said that the author has shown evidence that 'Mr. Bik's point is wrong' in only 10 cases.

PLOS ONE has organized a team of three editors dealing with issues of publishing ethics, and responds to issues raised by Mr. Biku and others. According to team member Renee Hoch, the process of requesting raw image data from authors questioned in a treatise and, in some cases, asking outside reviewers for their opinions, takes about four to six months per case. It will take. Of the treatises that Mr. Biku pointed out that the images were duplicated, about 190 were resolved by the team, 46% of them corrected, 43% were withdrawn, and 9% tagged 'express of concern'. It seems that it was attached. Only two cases were wrongly pointed out by Mr. Biku, 'When Mr. Biku raises an issue and we investigate, in most cases we agree with her,' Hoch said. Mr. says.

Dissatisfied with the fact that it takes too long to address a treatise issue, Bik may also share the issue on PubPeer or his Twitter account. In addition, Twitter displays multiple images used in the treatise, and frequently asks quizzes to guess which of the duplicate images is.

#ImageForensics AO / EB staining edition. Level advanced. #ImageTwin found three overlapping panels. Can you spot them? Pic.twitter.com/9cZy2F2FXV

— Elisabeth Bik (@MicrobiomDigest) July 4, 2021

Bik also pointed out a problem with a treatise published by medical information analysis company Surgisphere in 2020. As a result, the paper on the administration of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine to patients with new coronavirus infection (COVID-19) using Surgisphere data has beenwithdrawn.

At the same time that Mr. Biku's influence in the scientific community has increased, he has also increased the number of attacks on Mr. Biku on social media and editorial battles on Wikipedia. In May 2021, French infectious disease scholar Didier Raoult filed a complaint in a court in Marseille, suing Bik for harassment and attempted extortion. In response, Citizen4Science, a non-profit organization consisting of scientists and citizens, defended Mr. Biku, and thousands of signatures supporting him were collected, and the French National Center for Scientific Research also defended Mr. Biku. Was announced.

In recent years, some computer scientists have been developing software that uses artificial intelligence's image recognition capabilities to collate images extracted from papers against large databases and check for problems. Bik welcomes the advent of efficient image scanning programs, believing that computer programs will be able to check more papers than human power.

In addition, Mr. Biku said that he aspired to be an ornithologist when he was a child, observed birds with binoculars for hours and recorded the type of bird, but said that he is not good at remembering human faces. I am. Wellesley College psychologist Jeremy Wilmer tested Bik's abilities online and found that his 'face recognition' abilities were certainly below average, while memorizing and collating abstract images. It seems that the ability was very good, and this may have created the ability to detect duplicate images.

Related Posts:

in Science, Posted by log1h_ik