Experts say the meeting of sperm and egg is more like a job interview than a competition. What is the mechanism of fertilization, which is even more rigorous than a first come, first served race?

Fertilization of an egg is often likened to an epic swimming contest, with countless sperm sprinting toward a single egg. Live Science spoke to several experts about whether such a race actually takes place.

Do sperm really race to the egg? | Live Science

It's well known that sperm swim using tail-like flagella, but according to David J. Miller, a professor in the Department of Animal Sciences at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, most of the sperm movement is not due to self-swimming, but rather thanks to the female.

In a 1996 German

'The main movement of sperm is actually driven by contractions of the female reproductive tract. For example, the uterus contracts, which are very similar to peristalsis in the digestive tract and allow the fluids in the uterus to move about,' Miller said.

While the sperm move deeper into the uterus in this way, the egg that leaves the ovary must travel through the fallopian tube toward the uterus. In other words, the sperm and egg must move in opposite directions to close the distance between them. At this time, the egg, which does not have flagella, moves instead using cilia on the surface of the fallopian tube.

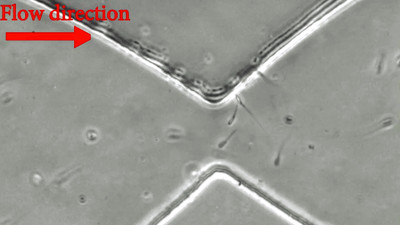

'The cilia beat to carry the egg along, but the sperm come from the opposite direction and have to fight their way against the current created by the cilia,' said Sabine Coel, professor of anatomy and developmental biology at University College Dublin's School of Medicine.

The sperm's flagella are what Koel calls 'the struggle,' and most of the sperm's effort is spent swimming up the inside of the tube rather than swimming back in. That's because if the sperm get too close to the wall of the fallopian tube, they can't move forward.

During this process, most of the sperm are filtered out, and in fact 70% of sperm never make it through the entrance to the uterus. 'Less than 1% of sperm actually make it to where the egg is, and at most only 2-3%. Most of the sperm are washed away, and some are eaten by immune cells in the uterus as foreign bodies,' said Koel.

Only a handful of sperm remain and reach the site where fertilization occurs, but unlike a race, it is not actually a first come, first served basis. This is because the sperm must undergo final maturation there. While waiting for maturation, the sperm may be washed away somewhere, or may be overtaken by another sperm that arrived later than them.

The few sperm that remain travel as far as possible, then attach themselves to the walls of the fallopian tubes and wait until the egg arrives. Here too, sperm are selected, and Miller says that the more normal-looking sperm are, the more likely they are to bind to the walls. Sperm that successfully stick to the walls have a metabolic advantage and therefore a longer lifespan. Then, once the egg arrives, the fallopian tubes ensure that only healthy-looking sperm are allowed to leave the walls.

While this selection system is not perfect – given that genetic diseases from both parents can be passed on – the female reproductive tract does its best to weed out less suitable sperm at every stage and ensure that only the healthiest sperm reach the egg.

Miller likens the system to a job interview: 'You need to be qualified to get the job, and the sperm of the qualified candidate has to be qualified at the exact moment the egg is released, which is when a position opens up and is advertised.'

Related Posts:

in Science, Posted by log1l_ks