What are the 'Rickover lessons' that show that government agencies can build large-scale industrial technology with the right team and culture?

Rickover's Lessons - by Lily Ottinger - ChinaTalk

https://www.chinatalk.media/p/rickovers-lessons-how-to-build-a

Rickover was born in Poland, which was then part of the Russian Empire, in 1900. He immigrated to the United States with his family in 1906. He enlisted in the United States Naval Academy in 1918 and, after graduating in 1922, began his naval career as an engineer officer.

In 1946, when plans were made to use nuclear fission energy to power submarines, Rickover went to work at Oak Ridge, the center of the Manhattan Project , which worked to build an atomic bomb during World War II. Through his work there and his interactions with physicists, Rickover quickly recognized the transformative potential of nuclear technology.

Convinced of the benefits of using nuclear power to power submarines, Rickover demonstrated strong leadership as head of the Navy's nuclear reactor division, successfully launching the world's first nuclear submarine in 1954. Many people did not expect nuclear submarines to become a reality so soon, but Rickover's achievements helped the U.S. Navy maintain military superiority for a long time. Rickover served on active duty for 63 years until his retirement in 1982, the longest-serving U.S. military officer in history at the time of writing.

'As America prepares for new strategic competition, Rickover's talk offers useful lessons for aspiring technocrats . Often, industrial policy is framed in legal terms, but Rickover shows that industrial policy is as much about strong leadership as it is about policy,' China Talk said.

by Wikimedia Commons

One of the defining features of Rickover's management was his thorough personnel management and training. Rickover spent a huge amount of time interviewing personnel, and during his active duty he had the final say on all naval officers who applied for service on nuclear submarines.

During one interview, Rickover asked a candidate who said he liked hiking if he had ever climbed a nearby mountain called 'Goat Mountain.' When the candidate answered that he hadn't, he told him, 'If you can bring me proof that you've climbed Goat Mountain by tomorrow morning, I'll hire you.' After learning that Goat Mountain was 'a structure in the middle of the goat enclosure at a nearby zoo,' the candidate jumped into the enclosure, climbed to the top, and asked someone nearby to take a photo as evidence. The next day, the candidate was hired by Rickover.

Rickover wanted people who could think for themselves, and to test the applicants' composure, he had them sit in a special chair that leaned forward like the woman in the photo below, while Rickover sat elevated during the interview.

Rickover placed emphasis not only on the hiring process, but also on continuing to train staff and building a talented workforce. He required employees to submit self-study plans for advanced subjects in metallurgy, physics, and chemistry, and required field trips to

Rickover also worked with MIT to develop a survey course in nuclear physics and a master's degree in nuclear engineering, and with Oak Ridge National Laboratory to develop a one-year nuclear science and technology curriculum called the Oak Ridge School of Reactor Technology (ORSORT), which trained personnel from military nuclear reactor contractors Westinghouse and General Electric , the Navy, and private shipyards.

Rickover also maintained direct communication with the contractors on site, all the sub-commanders of the nuclear power plant, and the officers involved in the project, and exercised strict supervision over the technical staff under him. He would collect carbon copies of all reports from the various teams and read them at home.

This strict management also extended to the private companies involved, with technical experts stationed on-site as 'project officers' to ensure that any problems would be reported to Rickover immediately. At this time, Rickover warned the project officers not to become too close with contractors or their families, as he was concerned that if a relationship developed between the person in charge and the person he was supervising, the reports would be less trustworthy.

Rickover's strict oversight led to the mass production of zirconium , used as cladding for nuclear reactor fuel rods. In 1949, the world was producing only a shoebox's worth of zirconium, and contractors hired by the AEC that year struggled to produce it. After a year of delays, Rickover received permission to manufacture zirconium at Westinghouse's facilities and worked with the Bureau of Mines to refine it.

As a result, Westinghouse was able to scale up its new zirconium refining process and produce several thousand tons. After the know-how for mass production was established, the AEC again put out bids for zirconium production. When the Secretary of the Navy later asked Westinghouse how they had scaled up zirconium production, they were told, 'Rickover made us do it.'

In a 1982 speech at Columbia University, Rickover said, 'A manager must pay attention to the details. If he doesn't think they're important, his people won't either. The devil is in the details. Attention to seemingly small things is hard and tedious, but I spend probably 99 percent of my time on what other people would call small things. Most managers would rather focus on lofty policy matters. But if you ignore the details, the project will fail. You can't fix the situation by injecting policies or lofty ideals.'

Rickover was a great people manager and technically savvy, but he also knew how to navigate large bureaucracies. He could tell the difference between useless rules and important rules. When a Navy officer in an interview once told him that he didn't want to keep a running report on the gas usage of the base's motorboats, Rickover told his boss to throw away the file on gas usage.

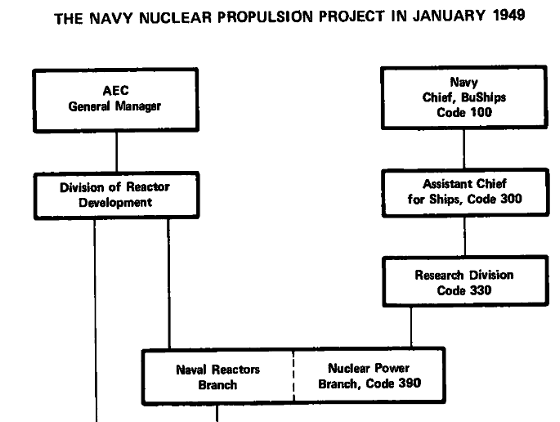

Many people, including the AEC, were skeptical of the nuclear submarine development project, wondering if it was really possible. Rickover found a way to avoid resistance by implementing his own bureaucratic innovations, placing himself in two command structures, the Navy and the AEC.

In fact, if you look at the organizational chart below that Rickover created, you can see that the Naval Reactors Branch and the Nuclear Power Branch are located under the AEC on the left and the Navy on the right. By being subordinate to two bureaucratic organizations, if the Navy shows reluctance to a certain instruction, they can reply, 'This is the AEC's priority,' and conversely, if the AEC resists, they can push through by saying, 'This is the Navy's priority.'

Rickover believed that even non-private government agencies could build incredible industrial technology at scale if they had the right team and the right culture. China Talk noted, 'While discussions in Washington DC often focus on regulations and money, Rickover's life story brings a unique, human-centered view of industrial policy that recognizes the importance of national capacity, technologists, and most importantly, public leaders with the vision and drive to build the technology.'

In a speech to Congress before his retirement, Rickover made the following comments:

'The obsession with the bottom line, the profit and loss statement, combined with the desire for expansion, has led to a decline in the number of businessmen who value traditional values. Accountability and power are increasingly separated, and financial skill is valued more than actual business knowledge and experience. This has created an environment in which most of the attention and effort is focused on short-term considerations, regardless of the long-term consequences.'

'Political and economic power over society, governments and individuals is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few large corporations and their executives. With control over vast resources, these corporations have effectively become another branch of government. They often exercise government power but without the checks and balances inherent in democratic systems.'

'With their ability to allocate funds, corporate executives often wield more power and influence over society than elected or appointed government officials, yet they bear no accountability and are free from public scrutiny. Woodrow Wilson , the 28th President of the United States, warned that economic concentration 'gives in the hands of a few men so much control over the economic life of the nation that they may abuse it and ruin millions.' His intent was to 'return the whole course of our national life to the standard which we first so proudly set and which we have always held in our hearts.' This statement is as applicable today as it is today.

Related Posts:

in Note, Posted by log1h_ik