In Finland, money was once physically cut in half to curb inflation.

by

In modern Japan, it is punishable by law to falsify banknotes by changing or cutting the denominations, but in 1945, at the end of World War II, Finland took a physical measure to devalue its currency by ordering its citizens to cut all high-denomination banknotes in half.

Moneyness: Setelinleikkaus: When Finns snipped their cash in half to curb inflation

https://jpkoning.blogspot.com/2024/11/setelinleikkaus-when-finns-snipped.html

Leikattu seteli on harvinaisuus - Taloustaito.fi

https://www.taloustaito.fi/vapaalla/leikattu-seteli-on-harvinaisuus/

Dramaattinen pakkolaina – sakset käteen ja seteli kahtia – Suomen MonetaSuomen Moneta – keräilijän kumppani, rahojen ja mitaleiden asiantuntija

https://www.suomenmoneta.fi/blogi/221-dramaattinen-pakkolaina-sakset-kaeteen-ja-seteli-kahtia

According to John Paul Koning, an expert on monetary economics, the Finnish government implemented Setelinleikkaus (banknote cutting), instructing citizens to cut their banknotes in half on New Year's Eve in 1945.

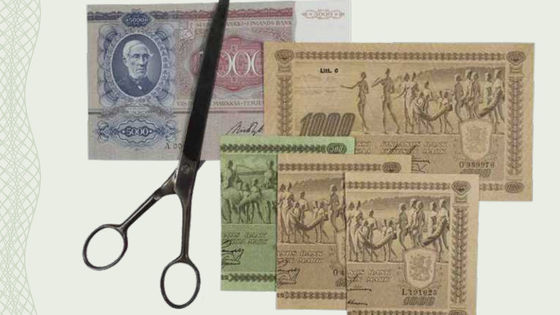

This meant that Finnish citizens were required to cut their high denomination banknotes of 5,000 , 1,000 and 500 markka with scissors early in the new year of 1946.

The cut notes could still be used to buy goods, but they were worth only half their face value - the left half of the 1000 markka note could only buy goods up to 500 markka in value, and the right half of the remaining note was treated as a compulsory loan to the Finnish government and was a bond that could not be used for shopping.

This was not an unprecedented move, and the policy was reportedly modelled on similar measures taken in Greece in 1922 and in Norway and Denmark in 1945.

As for why people bothered to cut paper money, economists Rudiger Dornbusch and Holger C. Wolf explained in a 1990

At that time, European citizens had accumulated a considerable amount of forced savings due to ``involuntary postponement of consumption'' caused by years of wartime production systems, price controls, rationing, etc., meaning that they had no choice but to keep money and could not spend it even if they wanted to.

After the end of World War II, people hoped to return to their previous lives, but with many factories destroyed during the war and production capacity reduced, serious shortages of supplies were predicted.

The fear was that a shortage of goods would lead to a sudden rise in the prices of goods, known as inflation.

The same thing is happening with the COVID-19 pandemic. The world economy is suffering from rapid inflation due to the lockdowns and supply chain disruptions from 2020 to 2021, followed by increased spending as lockdowns ended and unused aid money. In addition, Russia's invasion of Ukraine since 2022 has caused energy and food prices to soar, which can also be considered war-induced inflation in a sense.

Returning to Finland just after World War II, the Finnish government responded to the impending threat of hyperinflation by halving the purchasing power of its citizens and discouraging consumption by asking citizens to cut their banknotes in half and use the left half to shop, or to take them to the nearest bank to exchange them for new notes.

The right halves of the banknotes that could no longer be used were required to be registered with the government, and once registered, they were to be redeemed as Finnish government bonds with an annual interest rate of 2% in 1949. This meant that the Finnish government was trying to postpone half of the people's desire to spend for four years. In addition, there were suspicions that Germany was taking large amounts of money from Finland and making counterfeit notes, so it was thought that they wanted to switch to new banknotes as soon as possible.

In conclusion, the policy did not work and the Finnish economy suffered from inflation for some time afterwards, because the policy did not apply to deposits and only 8% of the total money supply at the time was covered by cash, leaving most of the monetary surplus untouched.

It is also believed that one of the reasons for the failure of the plan was that many Finns had foreseen the coming of drastic anti-inflation measures and protected their assets by converting their cash into savings or real estate.

by Antti Heinonen

Ultimately, the poor and those living in rural areas bore the brunt of the economic turmoil.

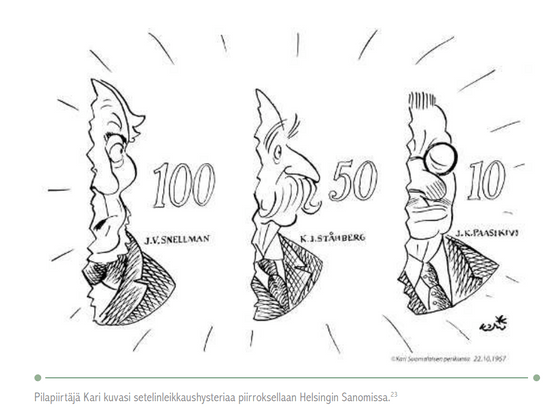

The bold policy of cutting the money in wallets in half and its failure left a strong impression on the minds of Finns as a result, and even when the devaluation of the markka was discussed in 1967, there were suspicious rumors circulating that the banknotes might be mutilated again.

Related Posts:

in Note, Posted by log1l_ks