Immune cells have long-term memory of pain experienced in childhood

Research has shown that pain experienced during the neonatal period can have long-term effects well into adolescence, suggesting that pain experiences alter the development of a child's pain response system at a genetic level, resulting in stronger pain responses later in life.

Macrophage memories of early-life injury drive neonatal nociceptive priming: Cell Reports

Immune cells carry a long-lasting 'memory' of early-life pain

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-04-immune-cells-memory-early-life.html

According to a paper published in the journal Cell Reports by a research team from Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, the changes in the pain response system occur in developing macrophages , one of the main components of the immune system. Macrophages are a type of white blood cell that ingests bacteria, denatured materials, dead cells, and other substances that invade the body.

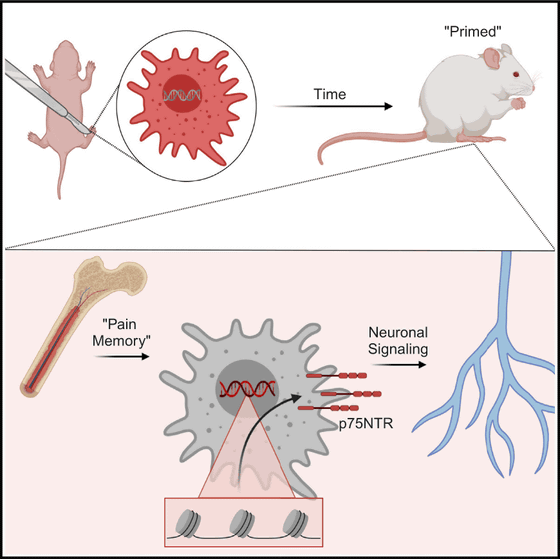

To investigate how neonatal pain affects later life, the team subjected neonatal mice to surgical injury and pain, then compared the injured mice to control mice and observed differences in their response to pain. Then, more than 100 days after the injury, they again subjected both groups of mice to pain and measured their response.

They found that in female mice, the group that received neonatal injury had a stronger and longer-lasting pain response than the control group. On the other hand, in male mice, there was no significant difference in pain response between the two groups. Furthermore, when the research team investigated the mouse macrophages, they found that

In female mice, the effects of pain memory were detected for more than 100 days after the initial injury. Bone marrow stem cells produce macrophages that are

The team noted that their findings suggest that simply changing the dose of painkillers may not be the answer to reducing pain, but rather that more specific, targeted therapies must be developed to prevent macrophage reprogramming in response to injury. Further research may lead to the development of techniques that can specifically block the p75NTR receptor in macrophages, but this approach will require significant research before it can be applied in humans in clinical trials.

Related Posts:

in Science, Posted by log1i_yk