The organizational trap that says, 'Everyone knows that they should try to prevent problems from occurring, but prioritizing short-term profits leads to big failures.'

If you encounter a problem and take the time to resolve it, you will receive a lot of praise and praise. However, if you predict and prevent problems in the first place, you may not receive a high evaluation because the threat of problems will not materialize. Regarding the contradiction in business, where everyone understands that it is better to make efforts to prevent problems from occurring, we tend to move toward dealing with problems when they occur, resulting in great disadvantages. Explained by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

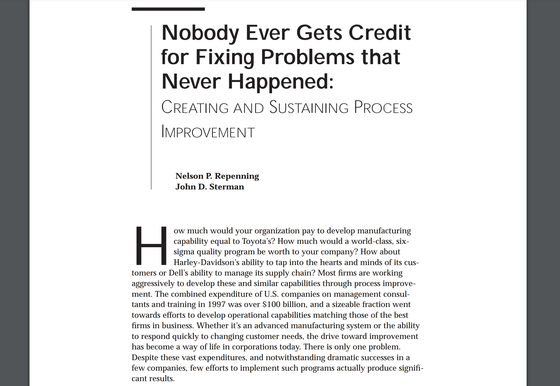

Nobody Ever Gets Credit for Fixing Problems That Never Happened: Creating and Sustaining Process Improvement

(PDF file)Nobody Ever Gets Credit for Fixing Problems that Never Happened: CREATING AND SUSTAINING PROCESS IMPROVEMENT

https://web.mit.edu/nelsonr/www/Repenning=Sterman_CMR_su01_.pdf

A paper published in 2002 in the IEEE Engineering Management Review , an American non-profit engineering organization, by Nelson Reppening and John Sturman of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology is based on interviews with real-life cases about fundamental problems in corporate organizations. The survey included.

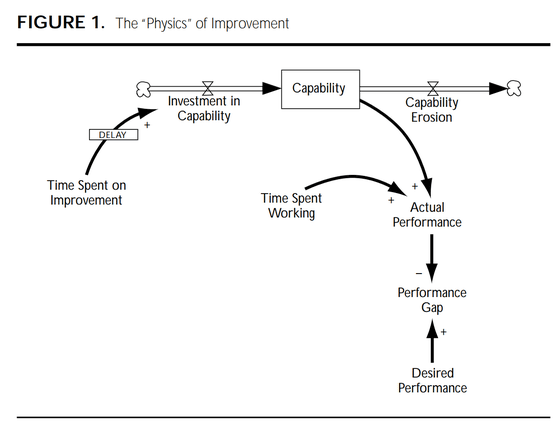

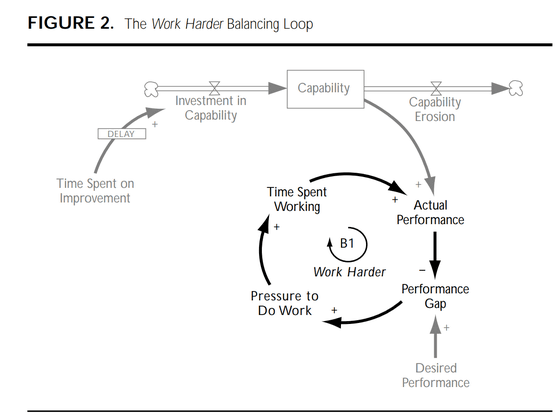

In the paper, organizational issues such as problem-solving performance and evaluation are illustrated in a 'causal loop' diagram. The following ``Causal Loop Diagram 1'' explains the basic theory that focuses on ``the amount of time spent on a task'' and ``the ability of the process used in that task'' to improve the problem-solving process. . If you start from 'Time Spent on Improvement' in the lower left, it will affect 'Actual Performance' over time via 'Capability'. On the other hand, the results of 'Time Spent Working' in the center of the image are almost directly reflected in 'Actual Performance.'

What is important to note here is that performance improves by improving both work time and work ability, but the rate of improvement is not equal. Increasing work time by 20% can be expected to increase production by 20% in most cases, but it is not possible to predict how much increase in working capacity will improve production. On the other hand, 'increasing working hours by 20% to increase production by 20%' assumes temporary overtime work to increase additional working hours, but improving working capacity After that, we can expect a permanent increase in production.

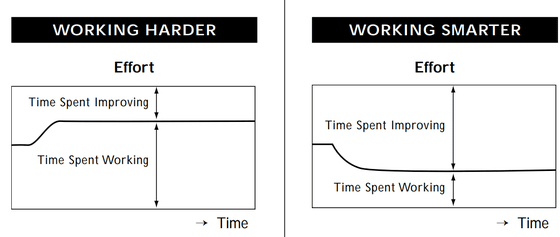

Figure 2 below shows the 'balancing feedback loop' that forms when you try to improve your performance by increasing your work time and 'working harder'. If you try to improve your performance by increasing your 'Time Spent Working,' your actual performance will move closer to your ideal result, but your next work goal will also increase your working time. You get stuck in a small loop where you have no choice but to deal with it by increasing it.

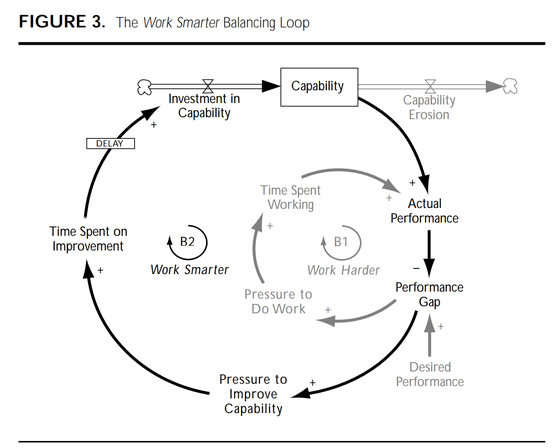

The second option to get closer to ideal performance is to improve your work ability and 'work smarter.' Figure 3 below presents a second balancing feedback loop in which managers launch process improvement programs, encourage new ideas, invest in training and Invest in 'Capability' by 'Spent on Improvement'. The results achieved thereby form a large loop in which the next step is to seek higher capabilities, and investment in capabilities continues. A loop that is larger than ``work harder'' indicates that ``it takes longer to see results after working on improvements.''

The approach to work capacity not only takes longer to produce results than simply increasing work hours, but also involves risks because it is less certain. Given these differences, 'it's no surprise that managers frequently adopt 'work harder,' even with some recognition that a permanently functional 'work smarter' approach is desirable.' points out in the paper.

The paper also suggests that we should consider how improvements in work time are linked to improvements in work ability when it comes to organizational contradictions. Increased pressure to improve performance is often met with immediate and reliable improvements in work time. However, improvements in working hours also have limits on overtime and holiday work, which takes time away from family and community activities. Furthermore, if you increase the amount of time you spend working at work, you will also need to cut back on time that could be spent improving your work ability, which will not have a positive impact on your performance in the long run.

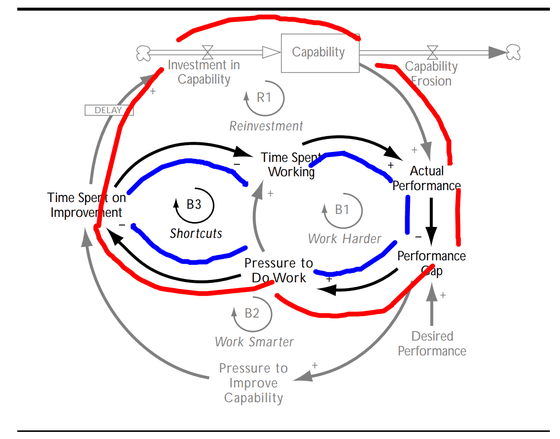

The paper idealizes a ``reinvestment loop,'' in which ``performance is improved by investing in improving abilities, and the time freed up from increased work efficiency is invested in further improving abilities.'' However, research on actual organizations shows that organizations that are able to engage in a reinvestment loop are exceptional, and that most organizations 'improve performance by increasing work time, and improve capabilities by reducing time.' It is said that a ``vicious cycle of reinvestment'' was in effect, in which they had no choice but to keep increasing their working hours because they could not invest in the work. The figure below shows the reinvestment loop, where the red line is a good loop that affects 'Capability' and the blue line is a bad loop that is addressed only by working time.

According to the paper, approaches that increase work time include cutting out meeting time for work, neglecting to pause machines for routine maintenance, and ignoring documentation requirements to just move on. , the overall working capacity will decrease over time. Researchers call the way increased processing power comes at the cost of deviating from standard routines and processes, cutting corners, and reducing time spent learning and improving. .

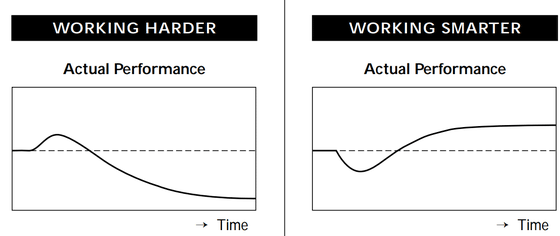

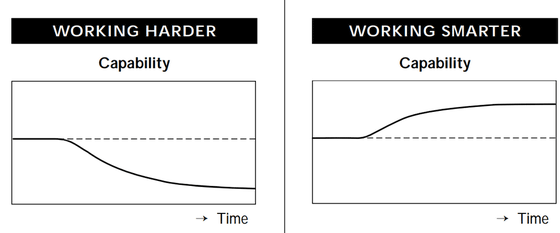

Below is a graph visualizing the difference between working harder (left) and working smarter (right). When it comes to 'actual performance,' working harder will temporarily increase your performance, but it will drop significantly over time. When you work smarter, your performance temporarily decreases for the amount of time you spend improving, but you can perform better on average over time.

Next, regarding 'effort,' it has been shown that overall effort decreases when approaches are taken to improve abilities.

The last one is a graph showing 'work ability'. When you work hard, your ability decreases significantly, but when you work smart, you need to improve your ability.

So, how should we actually improve our organizational systems? The paper discusses two past success stories.

Du Pont , one of the world's largest chemical companies, found in an internal survey in 1991 that it spends 10-30% more on maintenance than other major companies, but the compensation is small and overtime hours are long. ” It turned out that. The managers and teams tasked with improving this situation held repeated discussions and tests to identify areas that needed improvement and established the necessary system dynamics model . At this time, ``Chemical plants need to pay attention to equipment failures, but managers who are required to reduce costs try to reduce investment in maintenance and equipment upgrades, resulting in increased failures and inefficient operations.'' This creates a vicious cycle in which the cost increases.

As a result, Du Pont increased scheduled maintenance on its equipment. If planned maintenance increases, equipment will temporarily stop working, resulting in a significant drop in productivity in the short term. However, careful maintenance reduces unplanned breakdowns, and investing in high-grade equipment improves durability and reliability, and a virtuous cycle of reinvestment begins to operate. Although people may understand the idea of aiming for a good reinvestment loop by reducing short-term productivity, it is difficult to implement, so Du Pont held workshops through games and experimental learning, and by 1992, approximately Apparently 1,200 employees participated.

As another case, the paper summarizes the case of British Petroleum (BP), a British energy company. BP was founded in 1886 by John Rockefeller, but when it tried to cut costs in 1980, the organization fell into a trap, creating a vicious cycle of less planned maintenance, leading to more breakdowns and higher maintenance costs. I fell into it. BP, like Du Pont, engaged in an improvement program, and eventually 80% of all employees participated in the program, but in 1996 they announced that they would sell the refinery, but a buyer could not be found and the refinery closed. have become.

At the beginning of BP's improvement program, maintenance costs increased significantly, refineries closed, and many employees left the company. However, investment in maintenance eventually began to produce clear results, and in 1998 it was reported that the refinery had been rescued.

The paper points out that what is most necessary for organizational improvement is a ``mental model.'' It was clear that investments in improvement programs, workshops, and maintenance had a large long-term return, as in the case of BP, for example, the return on investment was calculated to be 30,000% per year. In addition, the necessary know-how, equipment, and resources are available on site. However, what was preventing them from starting to make improvements was the mental model that said, ``Even if you solve a problem that hasn't happened yet, you won't gain recognition or trust.''

'The most important thing is that people learn that they can make a difference,' the paper says.

Related Posts:

in Note, Posted by log1e_dh