The research of Kariko Catalin, who won the Nobel Prize for his contribution to the development of a new coronavirus vaccine, has been a series of hardships.

by

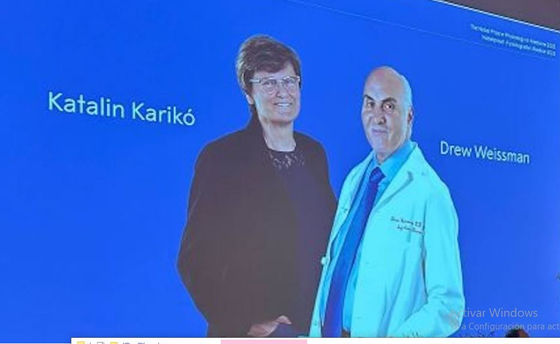

Kariko Katalin , who was the driving force behind the development of the mRNA vaccine that was put into practical use during the novel coronavirus outbreak and won the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Drew Weissman, has had a smooth research life so far. It wasn't a thing. The Daily Pennsylvanian, an overseas media outlet, has covered the numerous actions that the University of Pennsylvania has carried out over 30 years against Mr. Kariko.

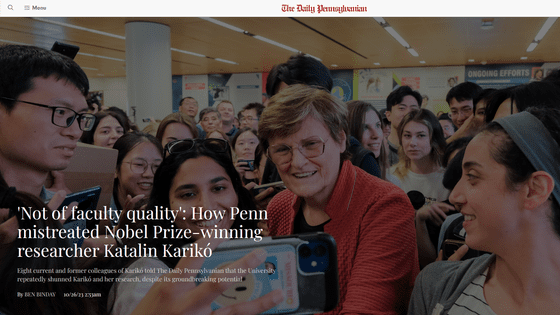

'Not of faculty quality': How Penn mistreated Nobel Prize-winning researcher Katalin Karikó | The Daily Pennsylvanian

https://www.thedp.com/article/2023/10/penn-katalin-kariko-university-relationship-mistreatment

Karikow, an adjunct professor of neurosurgery at the University of Pennsylvania, has

'We are proud of the extraordinary work that Mr. Karikow and Mr. Weissman have done that will benefit so many people around the world,' said University of Pennsylvania President Liz McGill. There is no better example than this,' he said, congratulating both men on their achievements.

However, Mr. Karikow faced various hardships before winning the Nobel Prize.

Mr. Karikow, who became an adjunct professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in 1989, was engaged in mRNA research under cardiologist Elliot Barnathan. However, his research was not recognized by the upper echelons of the medical school, and he was not allowed to use basic laboratory supplies such as purified water , and all of his applications for grants for his research were rejected. I did.

In 1994, the university notified Mr. Caricault that it had no intention of promoting him to the position of associate professor. Furthermore, in 1997, Mr. Barnathan, his supervisor, left the University of Pennsylvania, and Mr. Karikow found himself in even more trouble. ``Not only did I not receive grants or support for my research, but I also did not receive respect from people in positions of power, such as the upper echelons of medical school,'' Karikow recalls.

Still, thanks to his colleague David Langer, the chair of neurosurgery at the University of Pennsylvania, Karikow was able to remain at the university as senior director of research. Langer said, ``If Mr. Karikow had left the university in 1997, there may not have been a vaccine for the new coronavirus.Mr. Karikow is an incredibly hardworking and genius person, so one day he will be able to develop an mRNA vaccine. I was confident that I would achieve great results in this field.'

Mr. Karikow then met Mr. Weissman, who would later become a co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and the two began collaborating on research into mRNA technology. Despite a lack of research funding and pressure from universities, in 2005 Karikow and Weissman published the paper that would later win them the Nobel Prize. Weissman said, ``We began joint research on mRNA in the late 1990s and discovered what causes inflammatory responses and how to eliminate them, which we published in 2005. 'However, from around 2010, some researchers and companies began to become interested in the potential of mRNA vaccines.' Dr. Kariko added, ``When we discovered the potential of mRNA, we were filled with a sense of happiness that we could do anything.We were also confident that this discovery would lead to major advances in medical care in the future.'' I left a comment.

by

The University of Pennsylvania, which has obtained a patent for the mRNA technology developed by Kariko and his colleagues, will have final say on how to license the patent. Mr. Kariko and his colleagues insisted that the university own the patent in order to control the reporting system for future research, but this request was not accepted and the patent was sold to another company. it was done.

In 2010, Mr. Karikow made a request to the university to change him back from a research position to a teaching position. This request was accepted, but when Mr. Kariko returned to the laboratory in 2013, all the luggage was packed in boxes and placed in a corner of the room. With his research space removed, Mr. Kariko left the University of Pennsylvania and joined BioNTech, a German pharmaceutical company focused on mRNA-based technology.

'Many of Karikow's superiors at the University of Pennsylvania may not have been aware of the subsequent impact or success that her research had,' Langer said. 'Someone's value and ultimate success is not always immediately obvious. There is no guarantee that it will be.”

Robert Sobol, a former colleague of Dr. Karikow, said, ``I believe that this Nobel Prize award was brought about by Dr. Karikault's indomitable spirit.'' Mr. Karikault led many researchers to develop a vaccine for the new coronavirus. 'It became clear that we were 20 years ahead of the curve,' he says, praising the achievements of Mr. Kariko and his colleagues. In addition, former colleague David Scales said, ``Many research institutions, including the University of Pennsylvania, were struggling with funding issues, and as a result, researchers who left for other research institutions later worked for Mr. Karikow. I hope that this will give people an opportunity to think about leaving behind achievements like these.Specifically, I hope that the Nobel Prize awarded to Mr. Kariko and his colleagues will prompt a review of how research funds are allocated to researchers.' states.

Related Posts:

in Science, Posted by log1r_ut