The production of injections and drips continues to rely on ``live blood of horseshoe crabs,'' and there are signs of the emergence of new reagents that can serve as substitutes.

Vaccinations such as the coronavirus vaccine

Horseshoe crab blood is vital for testing intravenous drugs, but new synthetic alternatives could mean pharma won't bleed this unique species dry

https://theconversation.com/horseshoe-crab-blood-is-vital-for-testing-intravenous-drugs-but-new-synthetic-alternatives-could-mean-pharma-wont-bleed-this-unique-species- dry-214622

According to Christopher Whitney, an associate professor in the Department of Science, Technology, and Sociology at Rochester Institute of Technology in the United States, and master's student Jolie Cournell, Limulus Amebocyte Lysate is extracted from horseshoe crab blood. The substance called LAL) is essential for the production of injections and drips.

by

Since the mid-1800s, when injections began to be used medically, injections have historically caused a reaction called ``injection fever.'' This is caused by endotoxins synthesized by bacteria, which in high concentrations can cause shock and even death.

Later, in the 1920s, biochemist Florence Seibert discovered that the cause of injection fever was contaminated water contained in solutions, and devised a method to detect and remove the causative agent, which became the medical standard in the 1940s. It becomes.

This test, known as the rabbit pyrogen test, involves giving a drug to a rabbit intravenously and detecting that the drug is contaminated if it develops a fever.

by

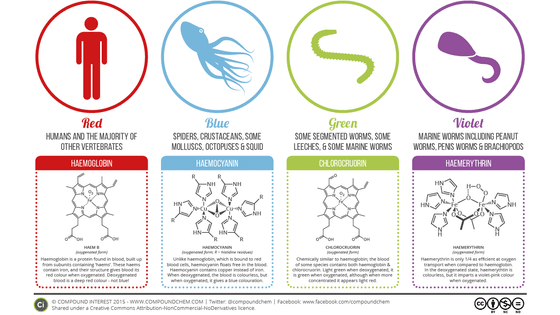

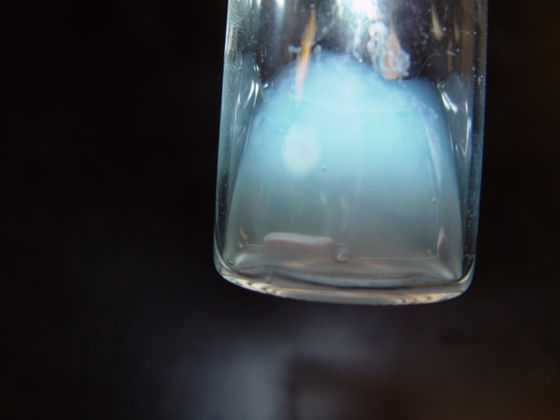

The change in testing method from rabbit to horseshoe crab blood was a coincidence. In the 1950s and 1960s, pathologist Fred Bang and medical researcher Jack Levin, who were studying horseshoe crabs at the Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts, discovered that the blue blood of horseshoe crabs mysteriously clots. I notice that it causes

Through a series of experiments, Bang and Levin discovered that endotoxin was the cause of clotting, and devised a method to extract LAL from horseshoe crab blood. The discovery of this LAL method is considered a breakthrough in medical safety in the 20th century.

By 1990, after improvements by researchers and biomedical companies and approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the LAL method replaced rabbit testing as the endotoxin testing method.

Horseshoe crab blood is needed to obtain LAL, but it is not known exactly how many horseshoe crabs, up to 30% bled alive, die after being returned to the sea, and estimates vary. The range varies from % to over 30%.

by

Moreover, the threat to horseshoe crabs is not limited to their use in the medical field. In the seafood market, horseshoe crabs are also valued as feed for farmed eels and shellfish, and it is said that more than 500,000 horseshoe crabs are killed every year in the two fishing industries.

Although a 2019 study on horseshoe crab fishing found no significant increase or decrease in horseshoe crab populations, conservationists have other concerns. In the United States, millions of shorebirds and plovers stop by the Atlantic coast each year for horseshoe crab eggs, traveling up to 9,000 miles between the southern tip of South America and the northern tip of Canada. Horseshoe crab eggs are a valuable energy source for the Great Sandpiper , which travels 4,480 km).

The Great Sandpiper was listed as an endangered species in 2015, largely because horseshoe crab fishing threatened its important food source. As medical demand for horseshoe crabs begins to match or exceed consumption by the fishing industry, conservation groups are asking the LAL industry to find other options.

View this post on Instagram

In response to these demands, the biomedical industry has been gradually developing alternative products. In the 1990s, researchers at the National University of Singapore invented and patented the first process to create synthetic endotoxin detection compounds using horseshoe crab DNA and genetic engineering techniques. The compound, called recombinant factor C (rFC), mimicked the first step in a three-step cascade reaction that occurs when LAL comes into contact with endotoxin.

Since then, several biomedical companies have developed their own rFCs and recombinant cascade reagents (rCRs), but LAL made from horseshoe crab blood remains the mainstream endotoxin testing method in medicine. .

The main reason for this is that the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), the drug regulatory authority, considers rFC and rCR to be 'merely substitutes for LAL,' and as a result, FDA approval has not progressed. thing. Conservation groups claim that ``LAL manufacturers are delaying approval of rFC and rCR to protect their own interests,'' but USP and LAL manufacturers ``take appropriate precautions to protect public health.'' 'I'm paying for it,' he argues.

This situation is gradually changing. Industry and authorities are increasingly aiming to minimize the use of horseshoe crabs, with Atlantic fisheries regulators considering new harvest limits for horseshoe crabs, and USP issuing guidance on genetically modified alternatives to LAL. We are currently formulating the following. Public comments on USP's new policy will be solicited in the winter of 2024, after which it will go into effect after review by USP and the FDA.

Whitney, who contributed this article to the academic media The Conversation, said, ``Policy-making on complex scientific issues that cut across various institutions is not easy. We believe that every step we can take will lead to important progress.'