Does everyone have a ``voice that talks to themselves in their head'', and what is analysis to study voices that others cannot hear?

There should be many people who read the contents of their thoughts in their heads, such as when they are thinking or reading. There is

Does everyone have an inner monologue?

https://www.livescience.com/does-everyone-have-inner-monologue.html

Frontiers | The ConDialInt Model: Condensation, Dialogality, and Intentionality Dimensions of Inner Speech Within a Hierarchical Predictive Control Framework

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02019/full

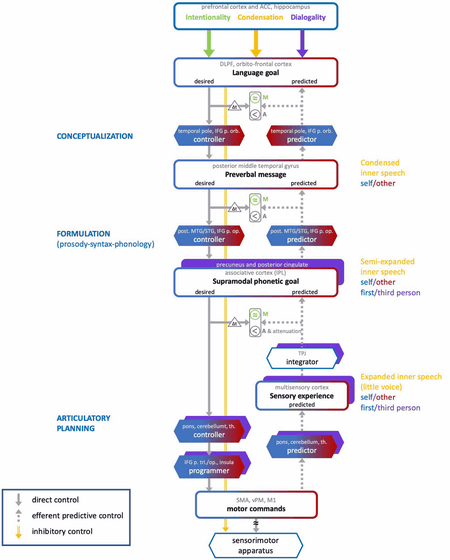

Levenbrück, a senior researcher in neurolinguistics and head of the language team at the Institute of Psychology and Neurocognition at CNRS, says of everyday monologues, can speak to itself, for its own sake, without articulation or sound.' A 2019 study published in Frontiers in Psychology , a peer-reviewed open-access journal of psychology, by Levenbrück and colleagues analyzes monologues in three dimensions.

First of all, the nature of the monologue changes depending on the degree of 'condensation'. Previous research has shown that a monologue, heard as a clear voice, goes through the stages of 'conceptualization' where the meaning and purpose are planned, 'formulation' where the concept is translated into spoken language, and 'clarification' as it appears in the speech. . At this time, thoughts are in a very 'condensed' state in the conceptual state, and it is thought that information is 'diffused' to make it into language and voice. In addition, former Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky said, ``Even in the monologue, which has been clarified as an inner voice, the words are omitted and the meaning is simplified compared to the words actually spoken as a conversation. There is a possibility that there is,' and in that sense, 'monologue is a condensed form that precedes verbal utterance.'

On the other hand, another study sees that monologue is a simulation of explicit speech production that includes all the stages toward utterance, and that only the movement of ``actually speaking'' is not performed. In conclusion, Dr. Levenbrück points out that monologues can be divided into cases of ``information that is more condensed than what is spoken'' and cases of ``information that is almost the same as what is spoken'' in terms of ``concentration''. I'm here.

Second, human monologues can have very complex 'interactivity', and it is debatable whether it is accurate to call all inner voices monologues. Mr. Lowenbrück states that monologues can be divided into three models when interactivity is taken into account. It is classified into self-corrected monologues and monologues as a dialogue between self and others.

Third, monologues can be analyzed according to their intentionality or intentionality aspects. Monologues can be intentional or unintentional. Among them, unintentionally heard voices are considered to be a kind of '

In Levenbrück's research, he proposes the ``ConDialInt (condensation-interactivity-intentionality) model'' as a neurocognitive model that analyzes the diversity along the three aspects of monologues. Based on this model, a more comprehensive neurocognitive model is being studied by accurately classifying the types of monologues by observing the movements of the mouth and throat when thinking and speaking. When this neurocognitive model is built, we can determine if we are actually speaking monologues in our heads.

The idea of questioning the belief that all people depend on monologues for thought and development began to emerge in the late 1990s, with Russell Hurlburt, a psychologist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas , calling buzzers We conducted a study in which participants were tasked with writing down their thoughts and experiences in their heads each time the buzzer sounded. In the research, regarding the command in the head 'I have to buy bread', I repeatedly asked 'Why did you buy bread?' 'Did you feel hungry?' 'Why did you choose bread?' Questions clarified participants' thinking. As a result, the participants answered, ``Every time I heard the beep sound that started observation, I was emitting a monologue as if there was a radio in my head,'' and compared monologues more than others. It seems that there were some participants who answered that they did not feel the monologue at all, and that they listened less.

'A long-standing complication in research on monologues is that people who participated in the study, even if they hadn't heard the monologues exactly verbally, were more likely to respond when asked to write them down,' said Lowenbrück. It's a fact that I can express my thoughts in words.I don't know if there was really a monologue there.'

In addition, Mr. Levenbrück points out that people who do not listen to monologues at all are the same as the state called 'Aphantasia' where people and landscapes cannot be imagined in their heads. ``The lack of aphantasia or monologues is not necessarily a bad thing,'' said Levenbrück, ``We value monologues, but we need a deeper understanding of monologues and the human thought process. So, I think it has important potential for learning methods and education in general, ”said the significance of the research.

What is 'Aphantasia' that you can not imagine people and landscapes in your head? -GIGAZINE

Related Posts:

in Note, Posted by log1e_dh