What was the case in the United States in 1970 when differences in political efforts, not geography, determined 'who gets measles'?

In recent years, there have been signs of

'A political division, not a physical one, determined who got measles and who didn't': Lessons from Texarkana's 1970 outbreak | Live Science

https://www.livescience.com/health/viruses-infections-disease/a-political-division-not-a-physical-one-determined-who-got-measles-and-who-didnt-lessons-from-texarkanas-1970-outbreak

In his book ' Booster Shots ,' pediatrician and infectious disease specialist Dr. Adam Ratner uses the example of the American city of Texarkana in 1970 to explain how it is political efforts, rather than geographical conditions, that influence the spread of infectious diseases.

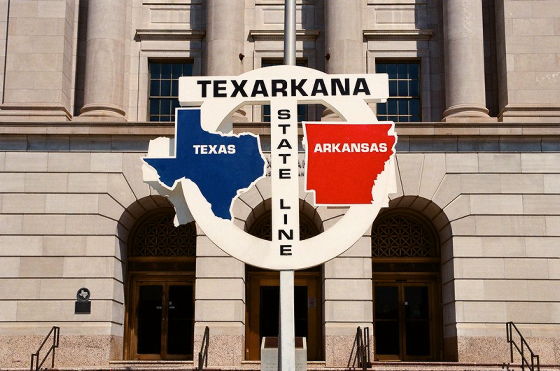

Texarkana is a city that straddles the states of Texas and Arkansas in the southern United States, with the Texas side of Texarkana and the Arkansas side of Texarkana forming one city. Texarkana residents and Arkansas residents live together in Texarkana, working at the same local companies, attending the same churches, and participating in the same community events.

But whether you live in Texas or Arkansas, separated by a single street, you have different states that run public schools and public health departments, making this a perfect setting to understand how policies, rather than geography, affect a resident's health.

By

In late June 1970, a 6-year-old boy in Texarkana was diagnosed with measles. This was the first known case of a measles epidemic in Texarkana that lasted for more than six months and during which more than 600 people, mostly children, fell ill with measles in Texarkana.

What made Texarkana different was that the Texas and Arkansas sides of the city, separated by a single street, had different approaches to measles vaccinations.

In Texas, children were not required to be vaccinated against measles before entering school, and there were no mass vaccination campaigns. Fewer than 60% of children ages 1 to 9 were immune to measles through vaccination or medical history.

Meanwhile, Arkansas made measles vaccination mandatory in schools and conducted mass vaccination campaigns targeting preschool and school-age children since 1968. As a result, it is estimated that 95% of children ages 1 to 9 were immune to measles.

The measles outbreak in Texarkana was strongly influenced by these differences in vaccination approaches: Of the 633 measles cases in Texarkana, 606 cases (about 96% of the total) occurred in people living on the Texas side of the state, while only a small number of people on the Arkansas side had measles.

This disparity in incidence rates occurred despite significant interaction between residents of both states, meaning Arkansas' aggressive approach to vaccination protected people who happened to live in Arkansas.

This example shows how vaccination doesn't simply prevent people from developing an infectious disease, but that countless political decisions, such as funding the public health sector or making vaccinations mandatory in schools, have real effects on people's health.

In Texarkana, the Texas and Arkansas sides have different approaches to Obamacare (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act) , which was introduced in 2014 with the aim of creating a universal health insurance system. It has been reported that the Arkansas side, which has accepted Obamacare, has a lower uninsured rate and fewer hospitalizations due to diabetes complications than the Texas side, which has rejected it.

Related Posts:

in Science, Posted by log1h_ik