It turns out that the metabolism can adapt to jet lag and sleep disruptions more quickly than the brain

The human body has

Short-term changes in human metabolism following a 5-h delay of the light-dark and behavioral cycle: iScience

https://www.cell.com/iscience/fulltext/S2589-0042(24)02386-1

Jet lag: your metabolism recovers quicker than your brain – new study

https://theconversation.com/jet-lag-your-metabolism-recovers-quicker-than-your-brain-new-study-243866

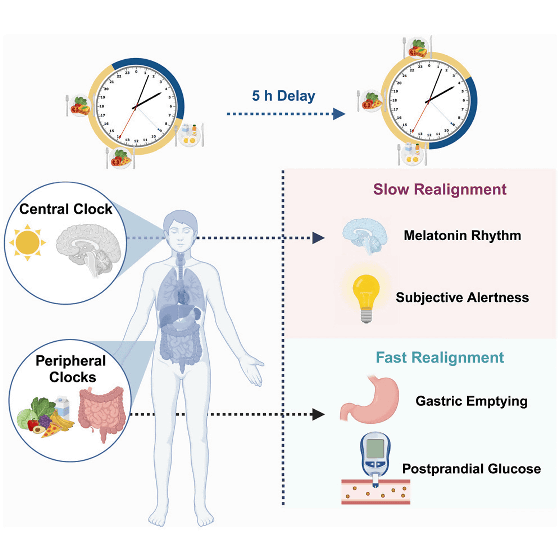

Although the human circadian rhythm is adjusted to suit the living environment and lifestyle, sometimes a mismatch between the circadian rhythm and the environment can occur due to shift work, jet lag, etc. This mismatch is called 'circadian desynchrony,' and past studies that shifted the circadian rhythm from the environment by 12 hours have reported changes in the subjects' metabolism and insufficient blood sugar control.

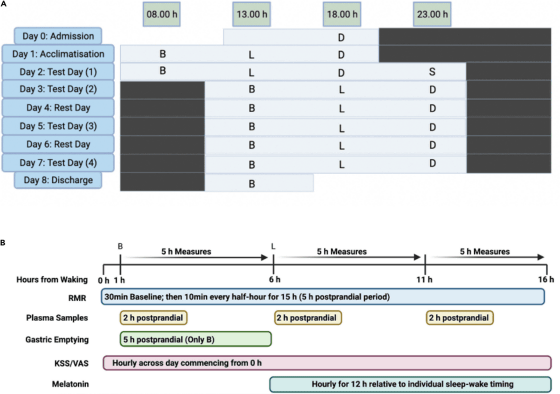

However, the effects of desynchronizing circadian rhythms that are less severe than 12 hours and the recovery from them are not well understood. So a research team from the University of Surrey in the UK conducted an experiment in which the environmental and behavioral patterns of male and female subjects were shifted by 5 hours.

In the experiment, participants were asked to follow their normal daily rhythm on Day 1, and on Day 2, their bedtime was delayed by five hours to induce desynchronization of their circadian rhythm. They then measured melatonin levels, a hormone that acts as a biomarker for the brain's clock, as well as subjective feelings of sleepiness and wakefulness throughout the day. They also collected blood samples to measure various metabolic biomarkers. The subjects were on average about 45 years old and tended to be overweight overall, but had no diagnosed health problems.

In the experiment, it was confirmed that as soon as a five-hour shift occurred between the circadian rhythm and the environment, sleepiness increased in the evening and alertness decreased. At the same time, melatonin levels also changed, and the body clock gradually adjusted, but it did not return to normal during the five-day experiment.

On the other hand, after the five-hour shift, numerous changes occurred in metabolism, including a decrease in energy consumption from meals, a delay in the time it took for the contents of the stomach to be delivered to the intestines after breakfast, and a readjustment of blood sugar and triglycerides.

In contrast to sleepiness and melatonin levels, all metabolic changes were fully readjusted over the course of the five-day experiment, with some changes readjusting within just three days, suggesting that metabolic recovery from circadian desynchronization is much faster than subjective sleepiness or the body clock.

The research team commented, 'Our study confirms that circadian desynchronization impairs human metabolism, but suggests that the metabolic disturbances are smaller than changes in sleepiness and alertness and are short-lived. This finding is relevant for shift workers and people around the world who frequently fly.'

Related Posts:

in Science, Posted by log1h_ik