China is strengthening its control over rare metals needed for key industries such as semiconductors, posing a threat to foreign companies.

As China deepens its political and economic conflict with the United States and its allies, it is strengthening its control over

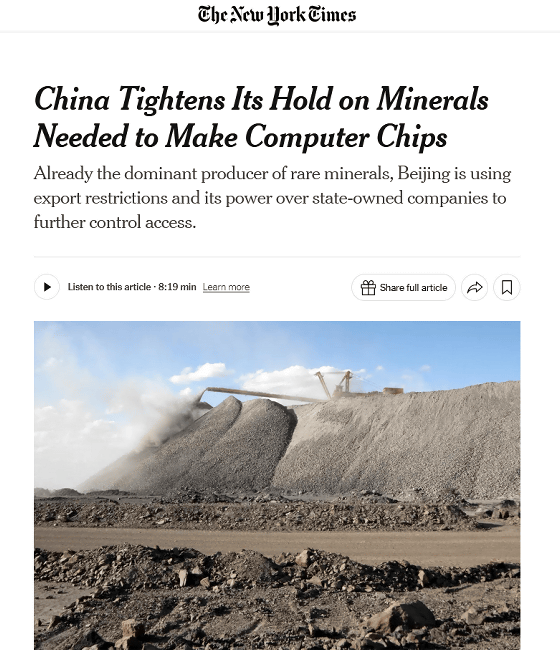

China Tightens Its Hold on Minerals Needed to Make Computer Chips - The New York Times

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/26/business/china-critical-minerals-semiconductors.html

China, a major producer of various rare metals, has enacted the Rare Earth Management Regulations from October 1, 2024. This regulation requires Chinese exporters of rare earths, a total of 17 elements including neodymium and dysprosium , to 'track how they are distributed through the European and US supply chains and report to the authorities.' This allows the Chinese government to know which overseas companies are obtaining rare earths produced in China.

Furthermore, starting September 15, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce began restricting the export of antimony, which is used in alloys, semiconductors, solar cells, military explosives, etc. In 2023, restrictions will also be imposed on the export of gallium and germanium, which are necessary for semiconductors, and China is retaliating against the US-led export restrictions on semiconductors by restricting the export of rare metals.

China's state security authorities have classified rare earth mining and refining as a state secret, and in September the Ministry of State Security announced that it had sentenced two rare earth industry managers to 11 years in prison for 'leaking classified information to foreigners.'

In response to these restrictions, the US government said in a September statement that 'China has monopolized markets for the processing and refining of key critical minerals, leaving America, our allies, and partners vulnerable to supply chain shocks and undermining our economic and national security.

Daan Di de Jong-ju, product director for critical minerals at London-based consulting firm Benchmark Mineral Intelligence , called the risk of supply disruptions a ' sword of Damocles hanging over the market,' and said China was ready to attack the supply chain at any time.

The New York Times points out, 'These materials are the focus of a broader battle between China and the United States over advanced technologies, including semiconductors used in artificial intelligence. Each side imposes export controls on components produced by its own countries while seeking to develop supply chains at home and abroad with trusted allies.'

Chinese rare earths are used in a wide range of products, including F-35 stealth fighter jets, wind turbines, electric vehicle motors, camera lenses, and catalytic converters for gasoline vehicles, and demand is expected to continue to increase as clean energy expands. One of the most important rare earths controlled by China is dysprosium, which is traded for more than $100 (about 150 yen) per pound (about 450 g). Dysprosium has been used primarily as an additive in powerful magnets installed in electric vehicles, but in recent years, its importance has increased as ultra-high purity dysprosium has come to be used in capacitors for advanced semiconductors.

Chinese refineries produce 99.9% of the world's dysprosium, most of it from a single refinery in Wuxi, near Shanghai. The refinery has been owned for many years by Canada's Neo Performance Materials , which has announced it will sell an 86% stake in the refinery to Chinese company Shenghe Resources by the end of 2024. Shenghe Resources' largest shareholder is China's Ministry of Natural Resources , making this a de facto nationalization by the Chinese government.

Neo Performance Materials has the right to sell rare earths to overseas customers for the next five years, and also owns another refinery in Estonia, but the Estonian refinery does not produce dysprosium. Other companies in Belgium, Australia, the United States and other countries have begun refining dysprosium, but there are few commercially viable dysprosium mines outside of China and Myanmar. In addition, rare earth refineries take years to operate, and it is quite difficult to produce the ultra-high purity dysprosium needed for computer chips that run artificial intelligence.

China's dominance in rare earth production is due to the fact that it is difficult for Chinese companies to compete with Chinese companies that have low production costs and are willing to incur losses, making it difficult for companies to invest in companies outside of China. China also has 39 universities with programs to train engineers and researchers in the rare earth industry, and refiners have the technology to extract more rare earths at lower costs. 'Chinese refineries literally have solvent extraction systems that are a generation ahead of foreign companies,' said Michael Silver, CEO of American Elements , a Los Angeles-based chemical manufacturing and sales company.

Related Posts:

in Note, Posted by log1h_ik