Experiments reveal that humans have a bias that tends to imagine 'better things'

Various biases are lurking in human thinking, and the breadth of thinking may be biased without knowing it.

Things could be better - by Adam Mastroianni

https://experimentalhistory.substack.com/p/things-could-be-better

One day, Mr. Mastroianni was discussing with a colleague the question 'Why do certain things (e.g. smartphones) look good and others (e.g. Congress) look bad?' Mr. Mastroianni et al. believe that feeling that 'A' is bad is because it is easy to imagine a better 'A'' than the current 'A', and feeling that 'B' is good is that He thought that it might be because it is difficult to imagine a better 'B' than the current 'B'.

For example, it is relatively easy to imagine a parliament with fewer dishonest members who unfairly exercise power than the current parliament. On the other hand, even if you try to imagine something better than the current smartphone, it's at most 'battery lasting', and it doesn't change smartphones dramatically, so smartphones are easy to be perceived as good. .

To test this hypothesis, Mastroianni conducted multiple experiments. First of all, as a preliminary preparation, 91 subjects recruited online were asked to list ``things they think about regularly'' and ``people and things they interact with'', and 52 items listed by 6 or more people were listed. . In the experiment, it was preferable that all subjects were able to think, so things that everyone did not have or had nothing to do with, such as 'girlfriend', were excluded. The final remaining items include 'your phone', 'people', 'economy', 'health', 'bank', 'bed' and 'work'.

In the first experiment, we randomly presented 6 items from a list to 243 newly recruited subjects and asked them, 'How could this thing change?' For example, if the selected item is 'YouTube', ask 'How could YouTube be different?' food be different? (How can food change?)' He asked. Variations on the answer might include 'YouTube could load faster' or 'Food could be more expensive'.

Then, if the change that the subject reported occurred, ``how much better/worse would it be?'' from ``-3 (very bad)'' to ``0 (neither good nor bad)'' to ``3 (very Good)” was evaluated in 7 stages. What Mastroianni and colleagues wanted to investigate was whether the change people imagined when asked ``how this thing could change'' would, on average, be good or bad. It was said that it was a point of becoming a thing.

As a result of the experiment, people overwhelmingly tended to respond to ``changes in the direction that things will get better''. An example of the subject's answer is as follows.

Question: 'How could your phone change?'

Answers: 'May be waterproof' 'May be flexible enough to bend' 'Brighter screen'

Question: 'How could your life change?'

Answers: 'I will be richer' 'I will be rich' 'I will be richer so I don't have to worry about finances'

Question: 'How could YouTube change?'

Answers: 'Stop pestering me every time I watch a video telling me to try a premium membership' 'No ads' 'Fix the algorithm so it doesn't screw up creators'

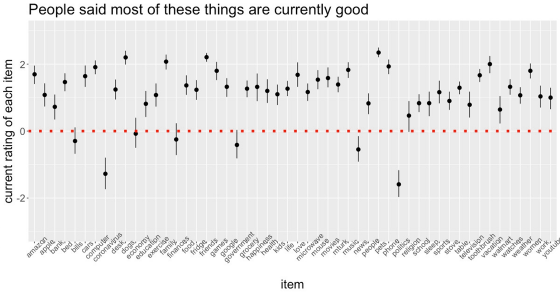

This tendency to imagine 'changes for the better' was seen in most of the items tested. Below is a graph showing how good/bad changes were on average for each item used in this experiment. The red dashed line is '0', above it represents a good change and below it represents a bad change. In most items, the subjects answered ``good changes'', and the average answers for ``bad changes'' were ``bills'', ``coronavirus'', ``government'', and `` It was limited to a few items such as news (news) and 'politics (politics)'.

In addition, the research team asked the subjects to rate the likelihood of the change they answered from 0% to 100%. Then, the most common evaluation was '0%', and the next most common was '50%'. This means that the subjects were not necessarily optimistic about the change they were responding to. In addition, 51% of the subjects answered at least one or more ``changes that make things worse'', so Mastroianni and others' questions implicitly asked for ``answers about changes in the good direction.'' Possibility of being misunderstood. It is said that sex is also low.

After that, Mastroianni and others conducted various experiments, and the wording of the question was changed to 'How could [ITEM] be better or worse?' ITEM] be worse or better? I tried asking questions in Chinese instead of English. As a result of conducting multiple experiments, it is reported that subjects tended to consistently answer ``changes in the positive direction'' in all cases. Surprisingly, it was confirmed that even if the subjects had depression, anxiety, or neurotic tendencies, they were more likely to respond to changes in the direction that things would get better.

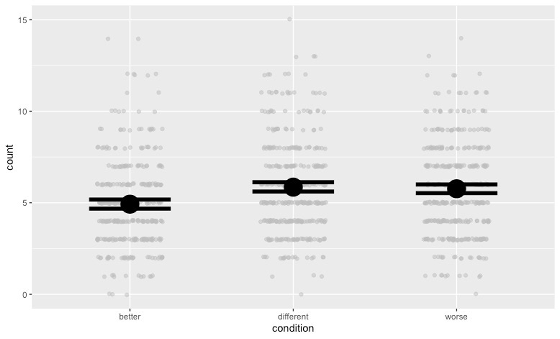

However, after the research team assigned the subjects to ``a group that responds to good changes'', ``a group that responds to bad changes'', and a ``group that responds regardless of whether changes are good or bad'', ``changes that can be considered for each item When we experimented with the condition that 'Bonus will be given if you answer faster and more answers', it turned out that 'the group that answers bad changes' can answer more. This does not mean that it is easier to think about good change than it is to think about bad change, but that it is somewhat difficult to think of good change. I'm here.

Mr. Mastroianni talks about the bias that tends to think about positive change in people, saying, ``Hungry and rained down hunter-gatherers imagined an environment with stable food and a roof, and later invented agriculture and architecture.'' Pointed out that it may be the result of natural selection. However, it is a mystery why this bias exists after all, and it will take a long time to understand.

Also, there is a possibility that the existence of a bias that tends to think about good changes is hindering people's happiness. For example, if you live in a cramped one-room apartment and imagine living in a larger room, even if you can move to a 3LDK apartment later, you may imagine living in a detached house or villa next time. Also, even if you get them, you may imagine a way to avoid property tax this time, and you may keep imagining 'better things' forever.

Related Posts:

in Science, Posted by log1h_ik