Researchers develop a battery-free pacemaker that breaks down in the body after a period of operation

Fully implantable and bioresorbable cardiac pacemakers without leads or batteries | Nature Biotechnology

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-021-00948-x

Scientists develop wireless pacemaker that dissolves in body | Medical research | The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/jun/28/wireless-pacemaker-dissolves-body

Millions of people have benefited from pacemakers since the first human pacemakers were embedded in 1958. According to a survey conducted in the United Kingdom, 32,902 people have newly implanted pacemakers between 2018 and 2019 alone.

However, not all patients need a permanent pacemaker, and some patients need a pacemaker only during periods of high heart risk, such as immediately after surgery. Already, there are pacemakers that can be removed after a period of time, such as infections through leads wired through the skin, accidental disconnection of external power and control systems, or the heart when removing the device. There is a risk of tissue damage.

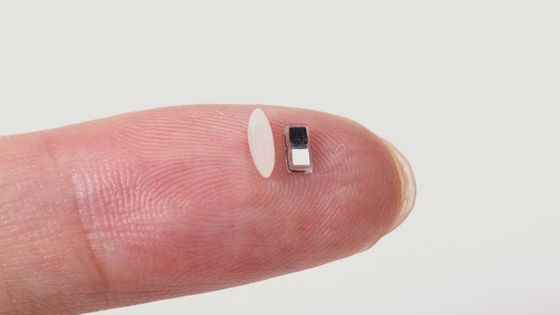

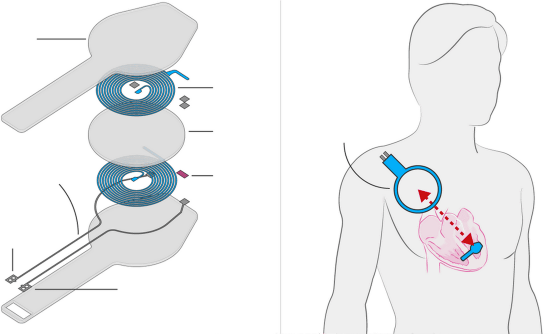

Therefore, a research team led by Professor John A. Rogers of Northwestern University in the United States has developed a battery-free pacemaker that is implanted in the heart and absorbed by the body after operating for a certain period of time. The pacemaker developed by the research team is composed of magnesium , tungsten , silicon , polylactic acid-glycolic acid (PLGA), etc., is thin and highly flexible, and weighs only about 0.5 g.

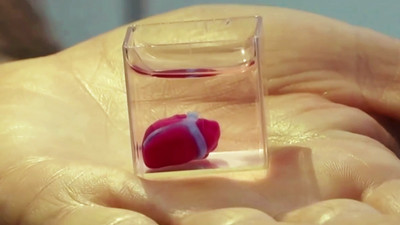

The pacemaker has a shape similar to a tennis racket as shown below, and has a mechanism to supply power wirelessly from an external device. The material of the pacemaker does not harm the body, but it causes a chemical reaction and dissolves over time, and is eventually absorbed by the body.

The research team has already tested the pacemaker in mice and dogs, as well as in sliced human hearts. In an experiment conducted on mice, the pacemaker operated for 4 days after implantation, and it started to dissolve about 2 weeks after implantation, and after 7 weeks, scanning the mouse's body did not reveal the existence of the pacemaker. that's right. The period during which the device operates and the time it begins to melt can be adjusted by fine-tuning the thickness of the parts.

'We tested the device on small and large animals, and on human hearts donated by donors, but not on living humans,' Rogers said. He said it could take a few more years for the pacemaker he developed to go through the regulatory process and be approved for clinical trials.

'This is an exciting and innovative development, temporary to the electrical transmission of the heartbeat after heart surgery,' said Sir Niresh Samani, a medical director at

Related Posts:

in Science, Posted by log1h_ik