Why are there 'witches' all over the world?

Most people living in Western civilization would answer 'I don't believe in witches who fly or turn into animals' if asked by someone. However, in reality, the belief that 'witches exist' is rooted in all sorts of places, from the islands of Indonesia to the cities of America. Gregory Force, a former professor of anthropology at the University of Alberta in Canada who studies witchcraft around the world, explains what

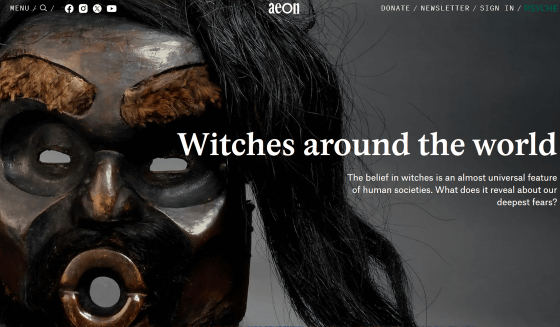

The universal belief in witches reveals our deepest fears | Aeon Essays

https://aeon.co/essays/the-universal-belief-in-witches-reveals-our-deepest-fears

Even though they are all called 'witches,' their form varies depending on the culture and region. For example, witches in Europe are thought to be beings who use tools to fly in the sky, transform themselves into animals, and hold nighttime gatherings. On the other hand, in Sumba Island , Indonesia, where Forth conducted fieldwork 50 years ago, witches were believed to be beings who transformed people's souls into animals and caused illness and death by eating those animals.

To consider the belief in witches, it is first necessary to define what a witch is. Anthropologists and historians define a witch as a person who is driven by malice and who intentionally harms people by mysterious means that are hidden and invisible to the naked eye, without using physical means. Ritual murder, cannibalism, and other acts that basically treat humans like animals are typical elements that make up a witch.

This allows witches from the Navajo and New Guinea in the southwestern United States to be treated together with European witches. It also allows witches to be considered behind cases such as the panic that occurred in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s, when a satanic ritual was performed at a daycare center and children were eaten, and the Pizzagate scandal that spread in 2016, when a pizza shop in Washington DC was the base of a secret satanic ritual.

In legends and stories, there are also 'good witches,' but this is due to the historical application of the Anglo-Saxon (Old English) word 'witch' to healers and benevolent magicians. Forth and other scholars therefore consider 'witches' to be evil beings who harm people.

The universality of witchcraft beliefs does not mean that witches are recorded in every culture on Earth, nor does belief in witches lead to witch hunts and panic. While Western satanic cases such as Pizzagate involved public accusations of witchcraft,

Some cultures don't even have witches at all, or even if they are familiar with them, they don't see them as a threat. For example, the Talensi people of Ghana don't believe that misfortune comes from the wickedness of others, but instead from just and all-powerful ancestors. In their society, illness and death are interpreted as just punishment for human actions.

However, the ubiquity of witches in many geographically, culturally, and temporally separated societies suggests that the idea that 'there is an evil person somewhere who tries to harm us by supernatural means' is persistent and persistent for humans. In other words, when misfortune or bad luck occurs to good people whose causal relationship is unclear, the existence of witches may have been believed in to explain that 'this is the work of an evil witch,' Fors argued.

The most famous of these cases is the Salem Witch Trials that took place in Massachusetts in the 17th century. At that time, Salem Village was a harsh environment where many of the residents were Puritans who had immigrated from England, and where conflicts with hostile Native Americans and French settlers sometimes occurred. In such an environment, there were successes and failures, and sometimes misfortunes occurred. It is possible that the belief in witches was strengthened to explain the situation.

What was the Salem Witch Trials, in which more than 100 people were accused of being witches? - GIGAZINE

Anthropologists who study witches have attempted to explain witch beliefs by focusing on social systems. In his 1937 book Witchcraft, Oracles, and Magic Among the Azande, anthropologist Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard , who studied the Azande people of Central Africa, described accusations and confessions of witchcraft as an essential element of Azande cosmology and a way of maintaining an ordered social life.

Azande witches were considered to have supernatural powers to harm people consciously or unconsciously, and were considered to be harmful simply by 'having ill will towards someone.' When an Azande person suffered from illness or other misfortune, they would seek the help of a fortune teller to reveal the witch's true identity and ask for a confession of being a witch. In many cases, the person who was confessed as a witch would confess to being a witch, explaining that they had no intention of harming anyone, and then the two would reconcile and the witch's troubles would be resolved.

Evans-Pritchard argued that Azande witches functioned both as an explanation for bad things happening to good people, and as a way to expose social tensions and conflicts between people and promote and maintain social harmony. Subsequent anthropologists, like Evans-Pritchard, have also interpreted witches as helping to stabilize social systems. For example, accusing someone of being a witch can help to resolve broken family or friendship relationships, or people can behave well out of fear of being harmed by witches, which leads to social stability.

However, because historians and anthropologists have focused on a single society, they have been unable to generalize witch beliefs across different societies. In fact, in some regions, it is primarily women who are considered witches, while in other societies, both men and women are accused of witchcraft, such as the Navajo in the United States and in parts of Africa. Similar variations are also seen in terms of age, social status, and wealth, and witch beliefs have been found in hunter-gatherer as well as agricultural societies.

Rodney Needham , Forth's supervisor at Oxford University, recognized the shortcomings of the sociological approach to witchcraft and proposed a new perspective. In his 1978 book Primordial Characters , Needham argued that to properly understand witches, we must study witches from different cultures and historical backgrounds.

Needham called the 'moral element' part of the widespread image of the witch, arguing that witches are seen as 'the absolute opposite of the moral human being.' For example, Ghanaian witches turn women's uteruses upside down to prevent pregnancy, while witches in early modern Europe, the Yoruba in West Africa, and the Mapuche in Chile steal men's penises and destroy their semen. This negates the normal process of human reproduction, and is one of the prominent expressions of the moral element image.

Other characteristics of witches that transcend cultures include being active at night, flying in the sky, turning into animals, and glowing at night. The element of 'glowing at night' in particular is seen widely from the Americas to Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific islands. On the island of Sumba in eastern Indonesia, witches are called 'people who glow, shine, and flicker at night,' and in the Twi language of Ghana, the practice of witchcraft is called a word that means 'shining.'

'Inversion,' where witches do things in the opposite way to what is appropriate or normal, is also a common feature. European witches, for example, hold their crosses upside down, perform rituals in reverse, dance in an unlucky counterclockwise direction, and do with their left hand what should be done with their right. Among the Nage people of Flores, Indonesia , where Forth conducted fieldwork, witches are described as 'dancing the wrong way' at cannibalistic feasts.

Needham says that these elements do not have to occur together, and Force agrees. In fact, none of the people who have been implicated in recent American devil worship have been noted to have been able to fly or transform into animals. Modern educated people have likely discarded these elements, as they are deemed impossible by modern physics. However, elements such as 'ritual murder,' 'cannibalism,' and 'reproductive interference (child sacrifice and promoting abortion)' remain as elements in condemning devil worship.

Unlike gods and ghosts, who are depicted as beings who act in the opposite way to humans, who take the form of animals, or who are mainly active at night, witches are also depicted as 'flawed human beings.' In most cases, witches are members of a village or family who speak the same language, but they are presented as the polar opposite of 'ordinary people like us,' by viewing them as morally alien and inhuman.

Some cognitive scientists see witches and magic as an evolutionary psychology derived from hunter-gatherer societies. The belief in the existence of unseen, malevolent enemies, internal or external, may have evolved as a psychological mechanism for survival in small, Stone Age communities.

Even if we isolate the ultimate causes of witchcraft, we won't immediately solve the social chaos and injustice that witchcraft accusations can cause, Forth argued, but the better we understand witch beliefs, the better our chances of containing and counteracting their worst effects.

Related Posts:

in Note, Posted by log1h_ik