The untold history of 18th-century machines that simulated human speech

In recent years, with the advancement of AI and synthetic voice technology, there has been remarkable progress in simulating voices that sound almost human. However, even in 18th century Europe, many technologies and machines that could simulate human voices were being developed.

“You Are My Friend”: Early Androids and Artificial Speech — The Public Domain Review

The first android with 'human functions' was created in February 1738. Engineer Jacques Vaucanson modeled it after Antoine Coysevaux's '

Many visitors to the trade fair were skeptical, believing that the android must have some kind of autonomous mechanism inside and was only pretending to play. However, the android was equipped with three pairs of bellows, lips, a tongue and padded fingers, allowing it to actually play the flute, which amazed visitors at the time.

According to Vaucanson, the android was powered by weights attached to two sets of gears: the lower set of gears turned a cranked axle, powering three sets of bellows that produced three different breath intensities, and the upper set of gears turned cylinders with cams that operated levers that controlled the android's fingers, tongue, and lips.

To design a machine that could actually play the flute, Vaucanson conducted detailed studies and observations of human flutists, and was able to replicate the techniques of a human flutist in an android.

In 1739, Vaucanson developed a machine that could play twenty minuets and other pieces using pipes held in the left hand, as well as a machine that played a drum worn on the shoulder.

In the mid-18th century, experimental philosophers and mechanists hypothesized that speaking was a bodily function similar to breathing and digestion, and predicted that speaking was an essentially organic process that could not be reproduced by machines. Philosopher and writer Antoine Cote de Gébelin pointed out that 'these phenomena, such as the vibration of the vocal cords, the trembling of muscles, and the effect of air on the sides of the mouth, can only occur in living organisms.' On the other hand, materialist Julien Offrey de la Mettrie, based on Vaucanson's machine, argued that 'the development of a speaking machine is no longer impossible.'

In 1771,

In addition, in 1778, the French abbot Michal donated a machine equipped with two artificial vocal cords to the Paris Academy of Sciences. The machine was equipped with two different doll heads, and it was possible to exchange words praising Louis XVI, such as 'The king gives peace to Europe,' 'Peace crowns the king with glory,' 'And peace makes the people happy,' and 'O King, beloved father of your people, their happiness shows Europe the glory of your throne.' In addition, writer Louis Petit de Bashomont points out that 'the conversation was hoarse and very slow.'

Nevertheless, scholars who investigated Abbot Michal's machine evaluated that it was 'made to imitate humans and is very close to the human vocal mechanism. ' After that, Abbot Michal received guidance from the Academie des Sciences and had an audience with Louis XVI.

Machines that simulate the human voice are called 'talking heads,' and C.G. Kratzenstein, who constructed artificial vocal cords made from organ pipes, and engineer Wolfgang von Kempelen have developed their own talking heads.

In the 1800s, the development of talking heads waned as a trend emerged to 'replicate the human voice by other means, rather than attempting to replicate the actual speech organs and physiological processes of speech.'

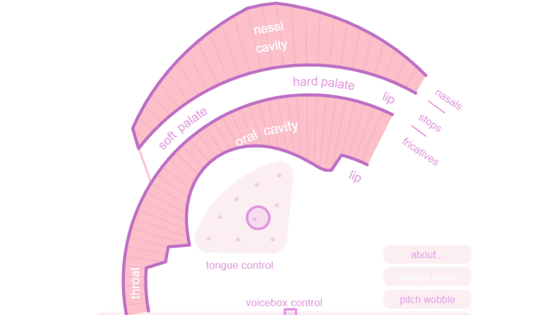

However, in the late 1840s, German immigrant Joseph Weber developed a talking head called the 'Euphonium.' The Euphonium had a realistic face, as well as bellows, vocal cords, a tongue, a variable resonance chamber, and an oral cavity with a rubber palate, lower jaw, and cheeks. The Euphonium could produce all vowels and consonants, and could be inflected by manipulating the 17 keys connected to a lever.

The euphonium was first exhibited in New York City in 1844, then in Philadelphia and in Paris in the late 1870s, but it never generated much interest and was quietly forgotten.

In the 20th century, with the development of science and technology, mechanical voice simulation gave way to the development of electrical voice synthesis technology, and simulation of the speech organs and speech process, such as vocal cord vibration, airways, flexible tongue and mouth, disappeared from the scientific stage.

Related Posts:

in Science, Posted by log1r_ut